Computer Systems and Low Level Programming

Storage Types

- auto: Default storage class. Stored on stack.

- extern: Global variable. Used for declarations only.

- static: Stored in data segment. Sort of like global

- register: Can be stored in register, but more of a suggestion to compiler.

Base Conversions

Decimal to Base B

- Divide N by Base B

- Remainder is one of the digits

- Set N = floor(N/B)

- Repeat until N = 0

Digits are in reverse

Base B to Decimal

- Use the following to convert from base b to decimal

$$ n = a_k b^{k-1} + a_{k-2} b^{k-1} … + a_{2} b^1 + a_1 b^0$$

Example

$$ 987_{10} = 9 \cdot 10^2 + 8 \cdot 10^1 + 7 \cdot 10^0$$

Binary to Hexadecimal

Each nibble (4 bits) is one hexadecimal digit

Example

0100 1110 1100 0011 to hexadecimal

4 E C B

Hexadecimal to Binary

Opposite of above

Binary to Octal

Every 3 bits is one octal digit

Example

110 111 011 001 011 to octal

4 7 3 1 3

Binary Addition

And determines whether a carry results

Xor is like an addition

Negative Number Representation

Signed Magnitude Representation

-

Just use the first bit as a flag to indicate whether the number is positive or negative

-

E.g.

- -1 is just 1001 for a 4 bit integer

- -4 is just 1100 for a 4 bit integer

-

Cons

- Wasted space by duplicate +0 and -0

- Addition of a positive number and the corresponding negative don’t yield an expected result

One’s Complement

- Take the bitwise inverse of the positive representation

- E.g.

- 1 is 0001, so -1 is 1110

- 4 is 0100, so -4 is 1011

Two’s Complement

-

Bitwise inverse of positive representation + 1

-

E.g.

- 1 is 0001, so -1 is 1111

- 4 is 0100, so -4 is 1100

-

Pros

- No duplicate 0 representation

- Addition of negative and positive numbers works

IEEE 754 Floating Point Representation

float: 32 bit (single precision)

- Sign (1 bit)

- Exponent (8 bits)

- Mantissa (23 bits)

- The fractional part of the number

Normalized Representation

- Sign (S): Either 0 or 1, for positive and negative respectively

- Exponent (E): Can’t be all 0s or 1s

- Mantissa (M): Fractional part

Decimal value = $(0)^{s} \cdot (1.0 + M) \cdot 2^{E-127}$

Range: $2^{-126}$ to $2^{127}$

- Used for most numbers

- Assumes Mantissa is 1. + M

- Bias is 127

Denormalized Representation

Exponent is 0b00000000

Formula:

$$ (-1)^{S} \cdot (0.0 + M) \cdot 2^{1-127}$$

- Used for values close to or equal to zero.

Special Values

Positive Infinity

S = 0

E = all 1’s

M = all 0’s

Negative Infinity

Same as above except S = 1

NaN

S = Either 0 or 1

E = all 1’s

M = anything except all 0’s

- divide by 0

- sqrt(-1)

Positive Zero

S = 0

E = all 0’s

M = all 0’s

Negative Zero

S = 1

E = all 0’s

M = all 0’s

Ranges

- Lowest positive normalized floating point: (1.0 + 0.0) * 2^(-126) = 2^(-126) = 1.1754943508 * 10^(-38)

- Lowest positive denormalized floating point: (0.0 + 2^(-23)) * 2^(-126) = 2^(-149)

- Highest positive normalized floating point:

- M set to all 1’s, and E set to 0b11111110 (E can’t be all 1’s cause that’s reserved for infinities and NaN)

- M = (1 - 2^(-23)) = 0.99999988079

- (1.0 + M) = (1.0 + (1 - 2^(-23)))

- E = (255 - 1) - Bias = 254 - 127 = 127

- Highest positive normalized = 1.99999988079 * 2^(127) = 3.402823466 * 10^38

- Highest positive denormalized floating point:

- M set to all 1’s

- M = (1 - 2^(-23)) = 0.99999988079

- (0.0 + M) * 2^(-126) = 0.99999988079 * 2^(-126)

- Machine Epsilon:

- Machine epsilon, $\epsilon$, is the smallest number such that $1.0 + \epsilon \neq 1.0$ on a machine

- $\epsilon = 2^{-\text{Num of bits for mantissa}} = 2^{-23} \approx 1.19 \cdot 10^{-7}$

- The distance between adjacent floats is not the same for all numbers.

- Example: The distance between 1.0 and the next cloest positive float is the machine epsilon (1.19 x 10^(-7)), but the distance between 6.022 * 10^23 and the adjacent float is around 3.6 * 10^16.

double: 64 bit (double precision)

- Sign (1 bit)

- Exponent (11 bits)

- Mantissa (52 bits)

Bias: 1023

- Provides Higher precision

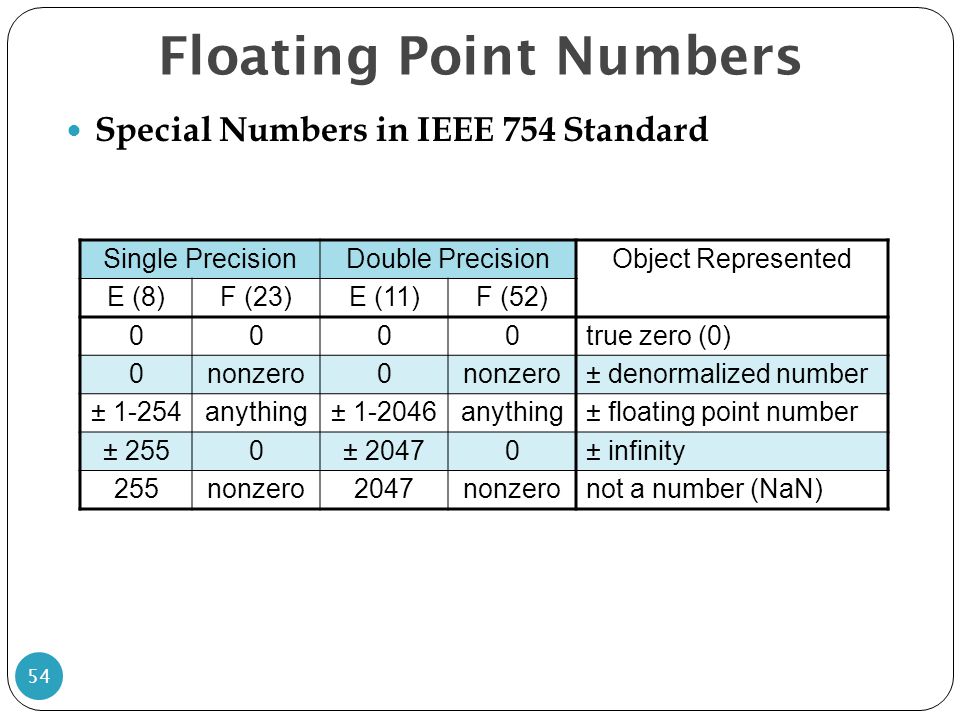

Summary of Floating Point Representations

Image from https://www.slideserve.com/yvon/arithmetic-for-computers

Convert Decimal to Floating Point

Example: Convert 131.3 to Floating Point Representation

First convert the part before decimal, so 131 to binary.

131 = 65 * 2 + 1

65 = 32 * 2 + 1

32 = 16 * 2 + 0

16 = 8 * 2 + 0

8 = 4 * 2 + 0

4 = 2 * 2 + 0

2 = 1 * 2 + 0

1 = 0 * 2 + 1

So 131 to binary is 10000011

Then convert 0.3 to binary

0.3 * 2 = 0.6 | 0

0.6 * 2 = 1.2 | 1

0.2 * 2 = 0.4 | 0

0.4 * 2 = 0.8 | 0

0.8 * 2 = 1.6 | 1

0.6 * 2 = 1.2 | 1

To convert fraction to decimal, multiply by 2 instead of dividing and the part before the decimal is the binary digit. Notice that the 0.6 * 2 = 1.2 repeats.

So 0.3 to binary is 01001100110011001 and so on, but truncate it so there’s 23 bits for the mantissa (24 bits total for the 1. + M)

Now you have 10000011.0100110011001100

Round the last digit to 1

Now you have 10000011.0100110011001101

Move the decimal point so that you have the form 1.M

$$ 1.00000110100110011001101 \cdot 2^7$$

Exponent is $E- 127 = 7$, so $E = 134$

Converting 134 to binary yields 10000110

Put it all together using the formula $(-1)^{S} \cdot (1.0 + M) \cdot 2^{E-127}$

$$E = 134$$

$$M = 00000110100110011001101$$

$$S = 0$$

So the binary representation is as follows:

S E M

0 10000110 00000110100110011001101

Assembly Instructions

Note that AT&T syntax is used

mov

mov src, dest

Types of moves

-

imm = immediate value (e.g. $0x4)

-

reg = register

-

mem = memory

-

Cannot do memory to memory transfer

-

Cannot do imm to imm

-

e.g. mov (%rax), (%rdx) is invalid

-

All other moves are valid (e.g. imm to reg, imm to mem, reg to mem, mem to reg, reg to reg)

Memory addressing mode

displacement(base_reg, idx_reg, scale) = base_reg + idx_reg * scale + displacement

- displacement: a constant that is usually 1, 2, or 4 bytes

- base_reg: any of the registers

- idx_reg: Any register except %rsp

- scale: 1, 2, 4, or 8

Example

- mov 8(%rdx, %rcx, 4), %rax

- moves the memory at address rdx + rcx*4 + 8 into the rax register

lea

lea src, dest

Set dest to src, where src is an address

Example

long multiply_12(long x)

{

return x * 12;

}

lea (%rdi, %rdi, 2), %rax # t = x+x*2 = 3*x

sal $2, %rax # return t << 2

- First computes x + x*2

- Then does an arithmetic shift right by 2 (multiply by 4)

cmp

cmp b, a

- Equivalent to (a - b) except without setting the result to a

- Used for comparison

- Sets ZF if a and b are the same

- Uses CF for unsigned comparisons

- Set when (a - b) < 0

- So when b > a

- Uses SF for signed comparisons

- Set when (a - b) < 0

- So when b > a

test

test b, a

- Equivalent to a & b without moving the result to a

- Sets ZF if a & b == 0

- Sets SF if a & b < 0

Floating Point Assemby

Floating Point Registers

- XMM Registers

- 16 total registers

- 16 bytes each

Floating Point Instructions

addsd %xmm1, %xmm0

- (Add scalar double)

Adds what’s in the xmm1 register to what’s in xmm0, and store the result in xmm0 - addss would just be for single precision floating points

Cache Memory

Notes based on https://youtu.be/chnhnxWIjgw

Cache Intro

- Without a cache, the cpu sends and receives data directly from memory by specifying an address

- This is relatively slow since memory is slow

- With a cache, there is a cache in between the CPU and memory. Caches are much smaller than memory but also faster. So when the CPU asks for data from memory by specifying an address, the cache can immediately return the data if that address is already in the cache.

- From the CPU’s point of view, nothing really changes with the cache since the CPU still sends/receives data by specifying an address

- From the memory’s point of view, nothing really changes as well with a cache since memory still receives/sends data when given an address.

- Although caching is used to describe a cache store between the CPU and memory, the concept of a cache is pretty general and can be used in the following context:

- CPU + Memory to Disk/Flash

- Browser to Internet

- Laptop to Distant Server

- Main Idea: Some data is important and access more often and is stored in cache while the other data is left in memory.

Intel i7 Memory Hierarchy

- CPU Core

- L1: Each core has one L1 instruction cache and one L1 data cache

- 32 KB

- 4 cycles

- L2: Each core has one L2 cache

- 256 kB

- 11 cycles

- L3: The L3 cache is shared between all cores

- 8 MB

- 30-40 cycles

- Main Memory

- 16 GB

- 50-200 cycles

Basic Concepts

When the CPU wants to READ some block

- Cache Hit: The cache contains the block we’re looking for

- Good and Fast

- Cache Miss: The block we’re looking for is not in the cache

- Bad and slow since we have to get the block from main memory

- Eviction / Replacement: New block loaded into cache, but other block is removed to make space for the new block.

- Evict the least recently used (LRU) block (block that hasn’t been used for a long time)

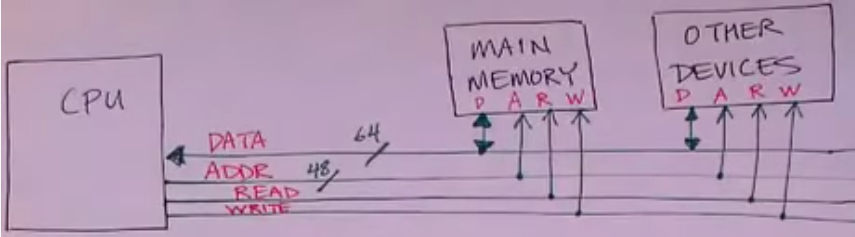

Control Lines for CPU and Memory

Source: https://youtu.be/rvTkRef4K48?list=PLbtzT1TYeoMgJ4NcWFuXpnF24fsiaOdGq

Locality

Typical Programs

- Use the same set of instructions over and over; most instructions not used

- Hot spots”/ Loop Bodies: Small number of instructions that are executed a lot

- Example of a hot spot:

for (i = 0; i < N; i++) {

for (j = 0; j < M; j++) {

... Loop Body ... <-- This is the hot spot since this gets executed a lot

}

}

- Working Set: Small set of instructions that are executed a lot over a long period of time (shifts over time)

- Hot spots also apply to data and not just instructions

The Principle of Locality

- Temporal Locality: If a byte of memory was used recently, it is likely to be used again

- Spacial Locality: If a byte of memory was used recently, nearby bytes are likely to be needed soon.

Locality applies to both data and instructions.

The Working Set

- Set of bytes that were used recently

- The set of bytes that will be needed soon

- This set can’t be known exactly, but in most cases it’s equal to the set of bytes used recently

- If the working set can be kept in the cache, then the program can run faster.

When we bring bytes into cache, we also bring in nearby bytes

Data Locality

- Nearby data is likely to be accessed soon

for (int i =0; i < N; i++) {

// Stride of 1 since you're going through the memory one element at a time

A[i] = 1;

}

for (int i = 0; i < N; i += 4) {

// Stride 4

// Not as fast, since the cache won't have as many nearby bytes since

// you're jumping through the memory

A[i] = 1;

}

This second program has less data locality, since the next item will be less likely to be in the cache and thus more misses.

2-D Arrays: Row Major Order

- Most languages store 2-D arrays in row-major order, meaning the rows are stored contiguously and then each row is also stored contiguously next to each other.

Example:

[1, 2, 3]

[4, 5, 6]

[7, 8, 9]

would be stored like this in memory, linearly:

[1, 2, 3] [4, 5, 6] [7, 8, 9]

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < 3; i++) {

A[i][j] = 1;

}

}

The above code has great locality since the stride is 1 due to how 2-D arrays are stored in memory.

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < 3; i++) {

A[j][i] = 1;

}

}

However, this code has a stride of 3 since it skips around and performs worse.

Writing

- Write-Hit: When cache contains the data we want to write to

- Write - Through

- Cache immediately writes modified block to memory

- Write - Back

- Cache waits; writes block to memory when the block is evicted from the cache

- Write - Through

- Write-Miss: When the cache does not contain the block

- Write - Allocate

- Read block into cache

- Update the copy in the cache

- Write - No Allocate

- Send the write on through to memory

- Do not load block into cache

- Write - Allocate

Typical Approach for Writing

- On Write-Hit use Write-Back

- Update copy in cache, but don’t update memory immediately

- Dirty Bit: Bit for each block saying that a block has been modified (dirty) or not modified (not dirty)

- Saves time. If bit not set, then there’s no need to write to memory

- On Write-Miss use Write-Allocate

- Load block into cache and update the copy in cache

- Do not immediately update memory

- Set dirty bit to 1 since the block has been modified

- Works well since if a block is used recently, it’s likely to be used again

2nd approach

- Use Write-Through and Write-No allocate

- Memory is not out of date while in 1st approach memory is out of date

- 2nd approach might be used if memory is shared between multiple CPUs

Cache Line

- Cache line: “The unit of data transfer between the cache and main memory.

- Example: If the cache line is 8 bytes in size on a 32 bit machine

- 8 bytes reserved for actual data.

- 29 bits for address of block stored (32 bits - 3 bits = 29 bits)

- The last 3 bits of the address are zero if the cache line is 8 bytes, so they don’t need to be stored

- Dirty Bit: 1 = Need to write back to main memory, 0 = never modified

- Valid Bit: Is the line full of data?

- Keeps track of whether the values in the cache are valid (e.g. when starting up, the cache will be full of garbage data)

- Also used when switching between processes.

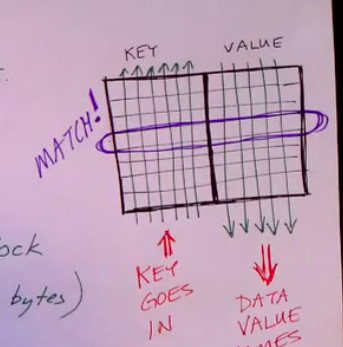

Associative Memory

-

Normal Memory:

- Address size: N bits -> $2^n$ values

- Guaranteed to give data for any address

- Requires too much storage to store all $2^n$ addresses since caches are small

-

Associative Memory/Cache

- Can be used for caches

- Key-value store (Key/Input: Address, Value/Output = Block Data)

- If the machine is 32 bits and the block size is 8 bytes, then the key is 29 bits

-

In this section associative memory and cache are used interchangeably

Fully Associative Cache

- “Any block can go into any cache line”

- Example:

- B = 64 byte block size

- L = Number of cache lines = 512 lines

- B* L = Size of cache = 32 KB (not including bits for non data)

- S = Set = 1

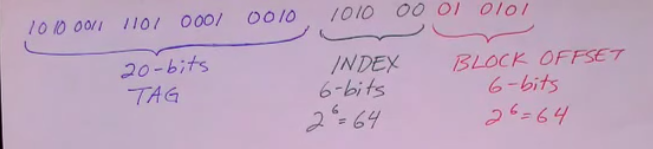

- 26 bits for key (called tag)

- 6 bits for block offset (2^6 = 64)

- Hardware Implementation

- Wires/lines for every bit of the tag cross with every cache line

- When a cache line’s tag matches the tag of the input, the hardware triggers the value wires to output the value corresponding to the tag

- Everything is implemented in hardware, which makes the cache faster

- Cache Operation

- Input: 32 bit address

- Extract 26 bit tag and 6 bit offset

- Send tag to associative memory (aka cache)

- IF MATCH:

- Get 64 byte data block from associative memory (cache)

- Use offset to extract the desired byte and send it to the CPU

- IF NO MATCH:

- Select block to evict (using LRU algorithm, which uses some extra bits in the cache line)

- If dirty bit set in the block to evict, write it back to memory

- Send the tag of the block we’re trying to get to main memory and get 64 bytes back

- Update cache line (key, data, dirty, valid)

- Extract the desired byte with the offset and send to CPU

- Problems: Works well for small caches, but slow for larger caches since you have to broadcast the full 29 bits of the key to all cache lines in associative memory

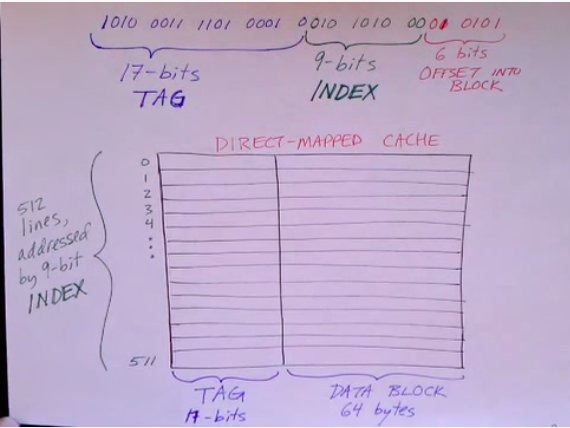

Direct Mapped

- “Each block can go into only one cache line” (e.g. Line 2 can only hold block 2 or block 512 or block 1026)

- Each cache line has the option of holding a set number of lines (but the line holds only one block, not more than one at the same time)

- Example:

- B = Block Size = 64 bytes

- L = Number of Lines = 512

- C = B*L = Cache Size = 32 KBytes

- Faster than associative lookup since a given block can only be in one line

- All we have to do to retrieve a block is retrieve a line and check if it contains our target block

- 2^9 = 512, so we can address any line with a 9 bit number

Cache Operation

- From the 32 bit address extract the 17 bit tag, 9 bit index, and the 6 bit offset

- Use index to find the correct line and read the line

- Compare the tag from the address to the tag in the cache line

- Same = Cache-Hit

- Different = Cache-Miss

- Use offset to get the right byte

- Problems: A cache line can only hold one block at a time, so if two blocks are in the working set and map to the same cache line, then cache thrashing occurs since the cache line is continually evicted and updated, decreasing performance.

The General Form Cache

-

Combines features of fully associative and direct-mapped caches

-

Has many small associative memories that can hold only a few lines

-

Example (8-Way Set Associative Cache):

- S = Sets = 64

- L = Number of Lines = 8 lines per set

- B = Block Size = 64 Bytes

- Total Cache size = 64 * 8 * 64 = 32 kB

Cache Operation

- Extract index: identifies which set to use

- Look at the set that the index maps to

- See if a line with a matching tag is in the set (set is associative, so it checks all 8 of its lines to see if the tag is in the set)

- Cache Thrashing is less likely to occur since each set can hold multiple blocks, even if blocks map to the same set

Cache Misses

Types of Compulsory Misses

- Cold Cache occurs when there is nothing in the cache when the program begins

Capacity Miss

- Cache is too small when it can’t contain the entire working set

Conflict Miss

- Plenty of room in cache, but 2 blocks in Working Set cannot be in the cache together (occurs in mappings like a direct-mapped cache)

Cache Unfriendly Code

- No locality: “Spaghetti code”

- Neural Network simulation

- Computer generated code

- Bizarre Algorithms

- Graph-like data structures

Cache Terminology

- Cache Hit

- Cache Miss

- Compulsory Miss

- Conflict Miss

- Capacity Miss

- Block

- Line

- Associative Memory

- Direct-Mapped Cache

- Write Through v. Write-Back

- Write-Allocate v. Write-No-Allocate

- Hit Rate v. Miss Rate

- Principle of Locality

- Spacial v. Temporal Locality

- Working Set

- Tag, Index, Offset

- Valid Bit

- Dirty Bit

- Stride

- Thrashing

Virtual Memory

Notes based on the lectures series by Professor Black-Schaffer: https://youtu.be/ZjKS1IbiGDA

I believe slides are based on Computer Systems by Bryant

Problems

- Problem 1: Not enough addressable memory

- Not really a big problem with modern computers

- 2^32 = 4 GB, so only around 4 billion addressable addresses for each program

- In reality around 2GB since other addresses are used by OS

- For a 32-bit processor, if you don’t have 4GB of RAM, the program could crash since it assumes it can access the whole 2^32 address space.

- Problem 2: Memory Fragmentation

- Holes in address space if you run multiple programs together and then quit one

- Problem 3: Programs overwriting/accessing each other’s memory

Solving Problem 1

- The problem is that every program uses the same 32-bit memory space.

- Virtual memory gives each program it’s own virtual memory space and uses mapping from a program’s virtual memory to physical memory (RAM).

- Virtual memory also allows us to map virtual memory to disk if we run out of RAM.

Solving Problem 2

- Mapping from virtual to physical allows program’s virtual memory to consist of multiple chunks of memory that might have holes or discontinuities

Solving Problem 3

- Each program has it’s own address space, so no overwriting of memory

- A possible downside is that program isolation might mean redundant memory spaces

- If programs have shared resources (e.g. fonts, graphics, icons, libraries), redundancy can be mitigated by just mapping the virtual memory spaces of both programs to the same physical memory space.

How Virtual Memory Works

- Virtual Memory: What the program sees

- e.g.

mov $0x4, %(eax)writes 4 to the virtual address stored in eax

- e.g.

- Physical Memory: The physical RAM of the computer

- Virtual Address (VA): What the program uses

- Physical Address (VA): What the hardware uses.

Translation

- Program executes a load or mov with a virtual address (VA)

- Computer translates the address to the physical address (PA) in memory

- (If the physical address (PA) is not in memory, the OS loads it from disk to memory and updates the map)

- The computer reads from RAM using the physical memory and returns the data to program

Page Table

- Page Table: The map from VA (Virtual Addresses) to PA (Physical Addresses)

- Problem: If we have a page table entry (PTE) for every virtual address, the number of entries will be the number of addressable virtual addresses. For MIPS assembly, only words are addressable, so the number of addressable addresses is the number of addresses divided by 4. So (2^32)/(4) = 2^30 = 1 billion addressable virtual addresses for MIPS, which means around 1 billion page table entires. This is a problem since we would need to store 1GB of mappings for every program if we wanted to use virtual memory.

- Solution: Divide virtual memory into chunks (pages) instead of words

- Page = Chunk of memory

- Page size: (Usually around 4kB or 1024 words per page) or 2MB

- Each page table entry now covers a range/chunk of data that is a page instead of just a word

- Tradeoff: less flexible with how to use RAM since you have to move a page at a time

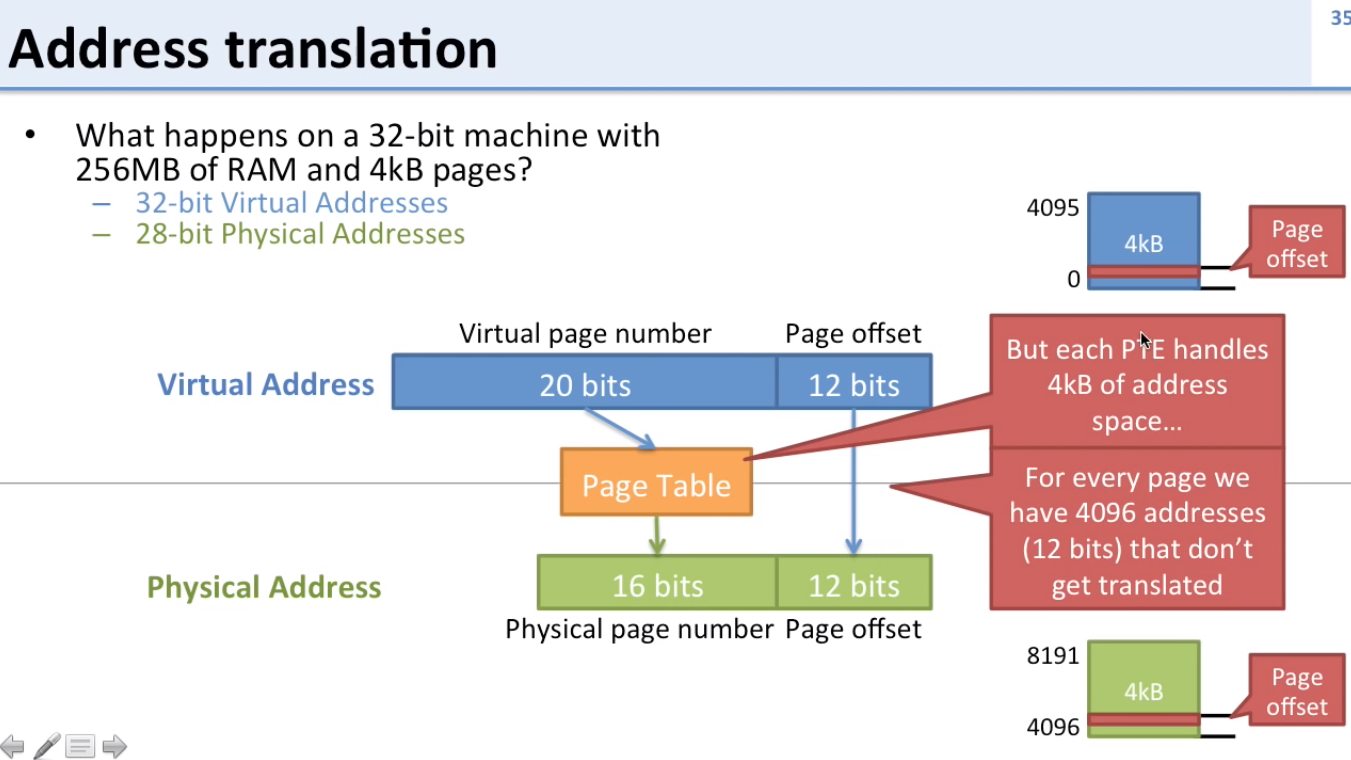

Address Translation Example 1

What happens if a 32-bit machine has 256 MB of RAM and 4kB pages?

- Page offset size for physical and virtual addresses stay the same

- Both page offsets are 12 bits: 4096 addresses that don’t get translated = 4kB = 2^12

- Page offsets don’t get translated by the page table, since they’re the same for both physical and virtual, only page numbers get translated

- 256 MB = 2^28 = 28 bits for total physical address

- 28 bits - 12 bits (for page offset) = 16 bits for physical page number

- 32 bits - 12 bits (for page offset) = 20 bits for virtual page number

-

Page offsets: tell us where in the page we’re at

-

Page number: Which page

-

In this example there are more bits for the virtual page number than the physical page number since the virtual memory size (32 bits) is greater than the physical memory size (28 bits)

-

In this example, you would map the rest of the virtual pages to disk once physical memory is exhausted

Address Translation Example 2

What happens if a 32-bit machine has 8 GB of RAM and 4kB pages?

- Page offsets are the same as above since we still have 4kB pages

- Virtual page numbers are the same as above since we still have a 32-bit machine

- The only thing that would change from the above example is the virtual page size with a virtual page size of 21 bits instead

- If you had one program running, you wouldn’t need to map to disk, but with 2 or more, you still might need to.

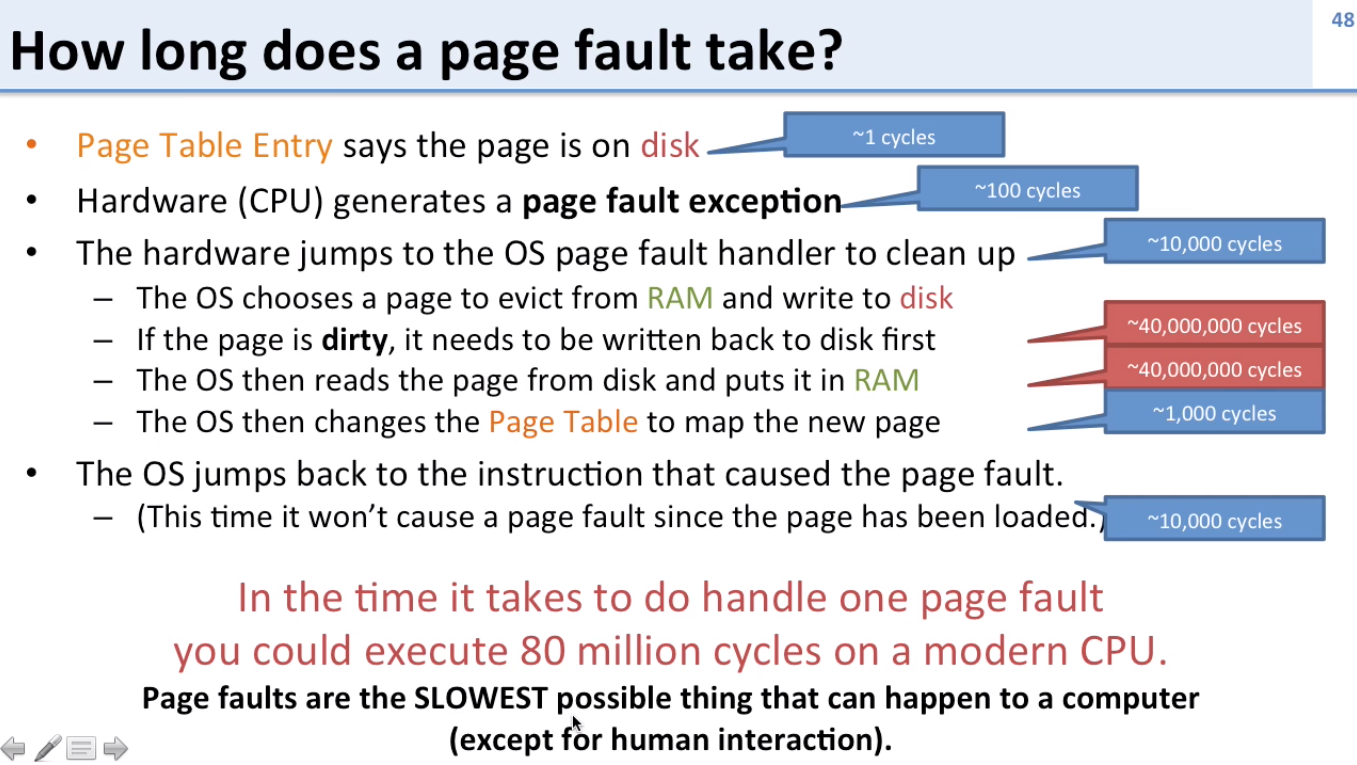

Page Faults

- Page faults occur when a page is not in RAM

What happens if a page is not in RAM?

- We know if a page is not in RAM if the page table entry (PTE) points to disk

- CPU generates a page fault exception

- Hardware jumps to OS page fault handler to clean up

- OS picks a page to evict from RAM

- If the page to be evicted is dirty, it is written back to disk first

- Otherwise, the page is just evicted

- Dirty just means that the data has been changed (written). If the data hasn’t changed since being loaded from disk, there’s no need to write it back to disk.

- The OS reads the page we’re trying to access from disk to RAM (where the previously evicted page was)

- The OS changes the Page Table Entry to map to the new page in RAM

- OS picks a page to evict from RAM

- The OS jumps back to the instruction that caused the page fault, but now the instruction won’t cause a page fault since the page is now loaded in RAM

A page fault takes incredibly long since disk is a lot slower than RAM

- Paging is good to have around, but shouldn’t be used often

- Having more RAM will make paging occur less often

- iOS: OS kills program if too much memory rather than paging

- OSX: OS compresses memory to prevent paging as long as possible

Memory Protection

- Each program has it’s own 32 bit virtual address space

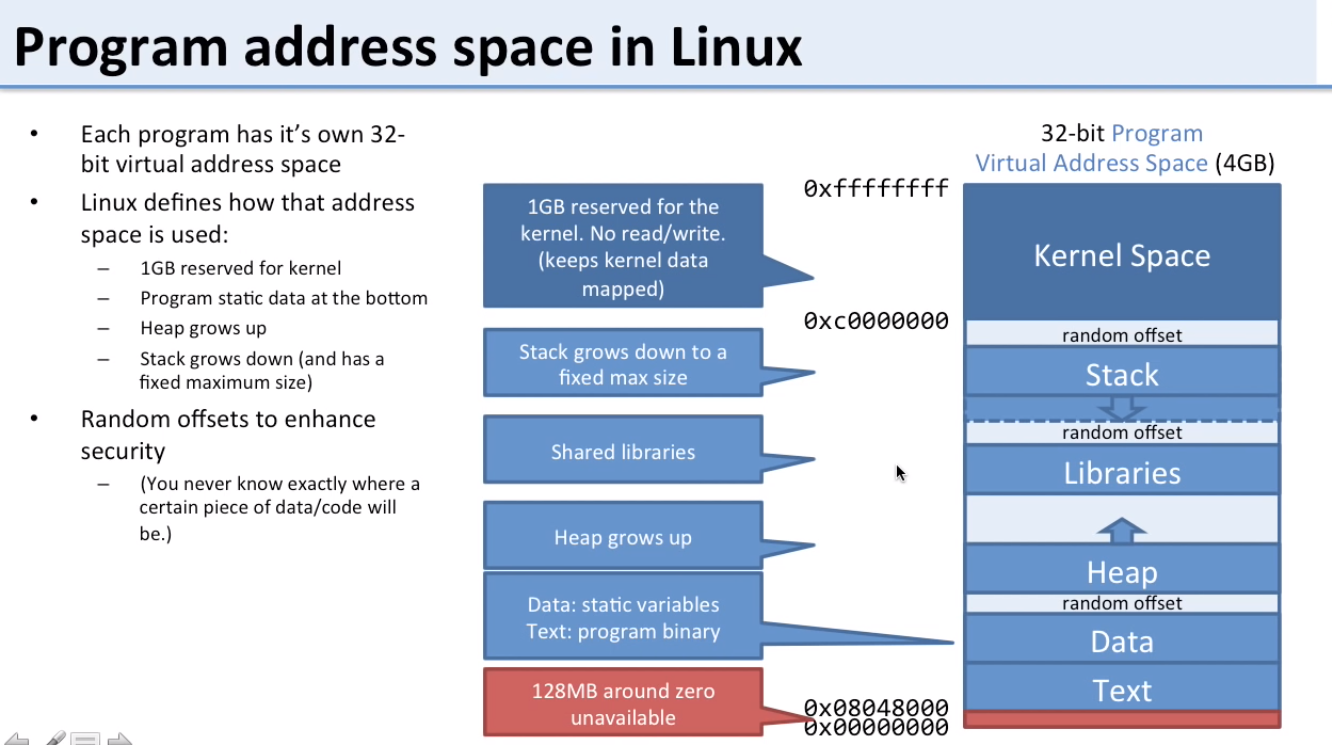

Program Address Space in Linux

- Assume top has the highest addresses

- First 1GB is reserved for kernel and can’t be accessed by program

- Next is the stack (grows down towards lower addresses)

- Next are libraries

- Next is the heap (grows up towards higher addresses)

- Next is the data segment (constants and global vars)

- Next is the text (program code)

- Finally there is 128 MB for IO at around address 0x00000000

- Random offsets for security

- Each process has its own Page table

- OS makes sure separate programs’ Page tables only share the same physical address when sharing memory/resources (e.g. libraries) is desired

Making Virtual Memory Fast

- Accessing memory with virtual memory needs the following steps:

- Access the page table in RAM

- Translate the address

- Access the data in RAM

This means there are at least 2 memory accesses when doing memory access with virtual memory

- To improve speed of virtual memory access you can’t add software, since even adding a few extra instructions per memory access would be slow

- The solution is through hardware like a (cache)

Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB)

- Page table is stored in memory

- Put in a TLB (cache) in the middle of the processor and memory to speed up lookup

- TLBs have to be small to be fast

- Separate TLBs for instruction (iTLB) and data (dTLB)

- 64 entries, 4-way (4kB pages)

- 32 entries, 4-way (2MB pages)

What can happen when we access memory?

Good: Page is in RAM

- PTE in the TLB

- Best case scenario for speed

- <1 cycle to translate then go to RAM

- PTE not in the TLB

- Poor speed (even a few cycles is detrimental)

- 20 - 1000 cycles to load PTE from RAM and then go to RAM

BAD: Page is not in RAM (Disk)

- PTE in the TLB (unlikely)

- Horrible speed

- 1 cycle to know if PTE is on disk

- ~80 M cycles to get from disk

- PTE is not in TLB

- (slight more) horrible

- 20-1000 cycles to know if PTE is on disk

- ~80M cycles to get from disk

Making TLBs better

- Make pages larger

- TLBs can reach more data since fewer pages are needed to cover data

- Add a second TLB that is larger, but a bit slower

- Have hardware to fill the TLB automatically

- Called a hardware page table walk

- Hardware does the work instead of the OS/software

TLB Usage Scenarios

- Empty TLB (Miss)

- Look in TLB and find it’s empty

- Just look for physical address that corresponds to virtual address in memory (RAM) and add an entry in the TLB

- TLB Hit

- Just look at the TLB and find a matching entry for virtual address and use that to translate

- Best Case

- TLB Miss

- Look in TLB and find no entry

- Go to PTE in memory (RAM) and update the TLB

- TLB Miss & Evict

- Look in TLB and find no entry and also find that TLB is full

- Kick out the TLB entry that’s been used the least recently (LRU)

- Find PTE and add to TLB

- Use TLB entry to do translation

Multi-Level Page Tables

Problem: Page Table Size

- For 32-bit machine with 3kB pages:

- 1 M Page Table Entries (32 bits - 12 bits for page offsets = 20 bits, 2^20 = 1M)

- Each PTE is about 4 bytes (20 bits for physical page + permission bits)

- 4MB total

- 4MB for each Page Table is problematic since we each program needs its own page table

- If we have 100 programs running, we need 400MB of memory just for the page tables

- We can’t swap the page tables out to disk since there would be no way to accessing the page tables on disk without page tables to translate

Solution: Multi-Level Page Tables

- Have a 1st level page table that has PTEs pointing to other page tables

- 1st level page table must be in main physical memory

- 2nd level page tables can be stored on disk as long as above is true

Sample Question 2

With multi-level page tables, what is the smallest amount of page table data we need to keep in memory for each 32-bit application?

- We need the 1st level page table in main memory

- We also need at least one 2nd level page table in memory to actually do something useful, since the 1st level page table only helps us find other page tables

- The 2nd level page table is needed to actually translate memory addresses

- 4kB + 4kB = 8kB is needed per application

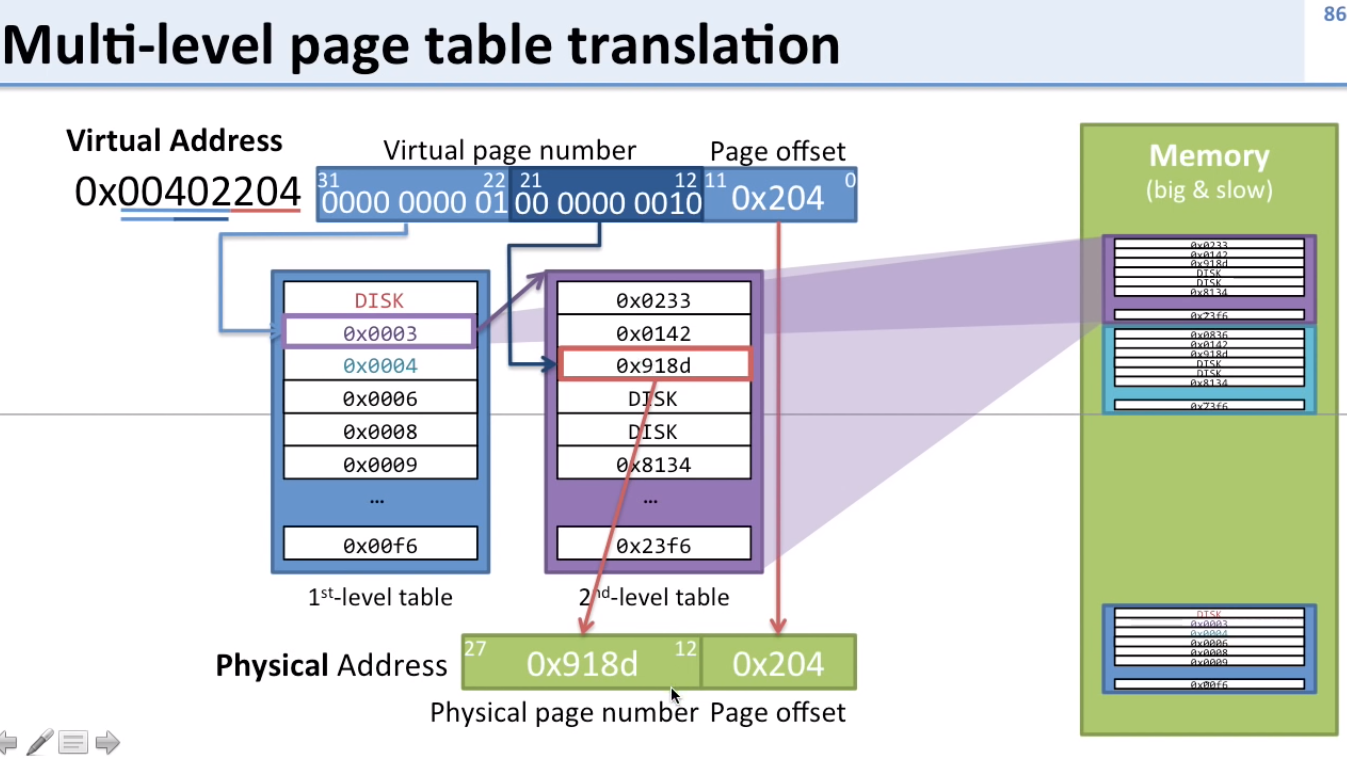

How multi-level page tables translate virtual to physical

- Split virtual page number (usually in half)

- First 10 bits are to choose which 2nd level page table to go to from the PTE in the 1st level page table

- Next 10 bits are to choose the physical address to go to from the PTE in the 2nd level page table

Sample Question 2

- If a computer is running 100 applications with a 2-level page table, how much memory is needed in RAM?

- 800kB = 100 * (4kB + 4kB)

- For each program a 1st level page table and a 2nd level page table is needed

- 800kB is much better than the 4MB needed before

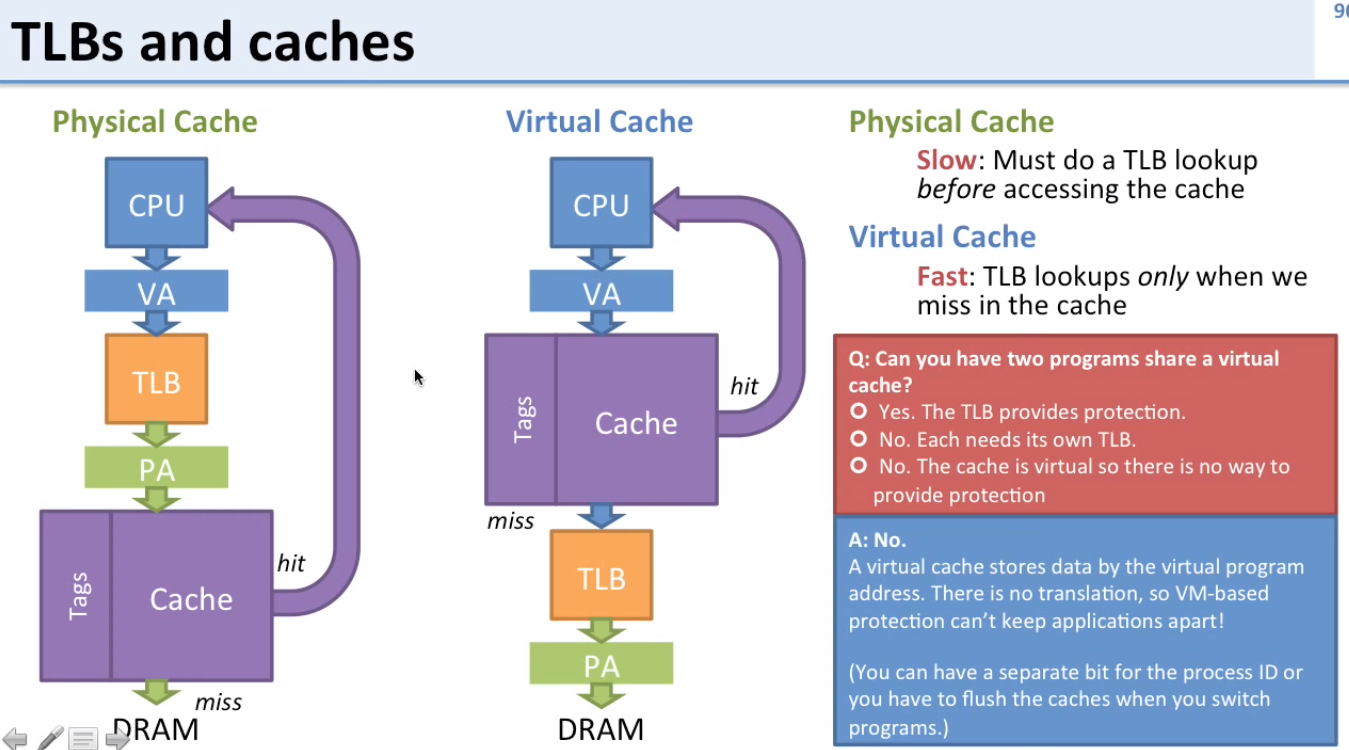

TLBs and Caches

Naive Cache approaches

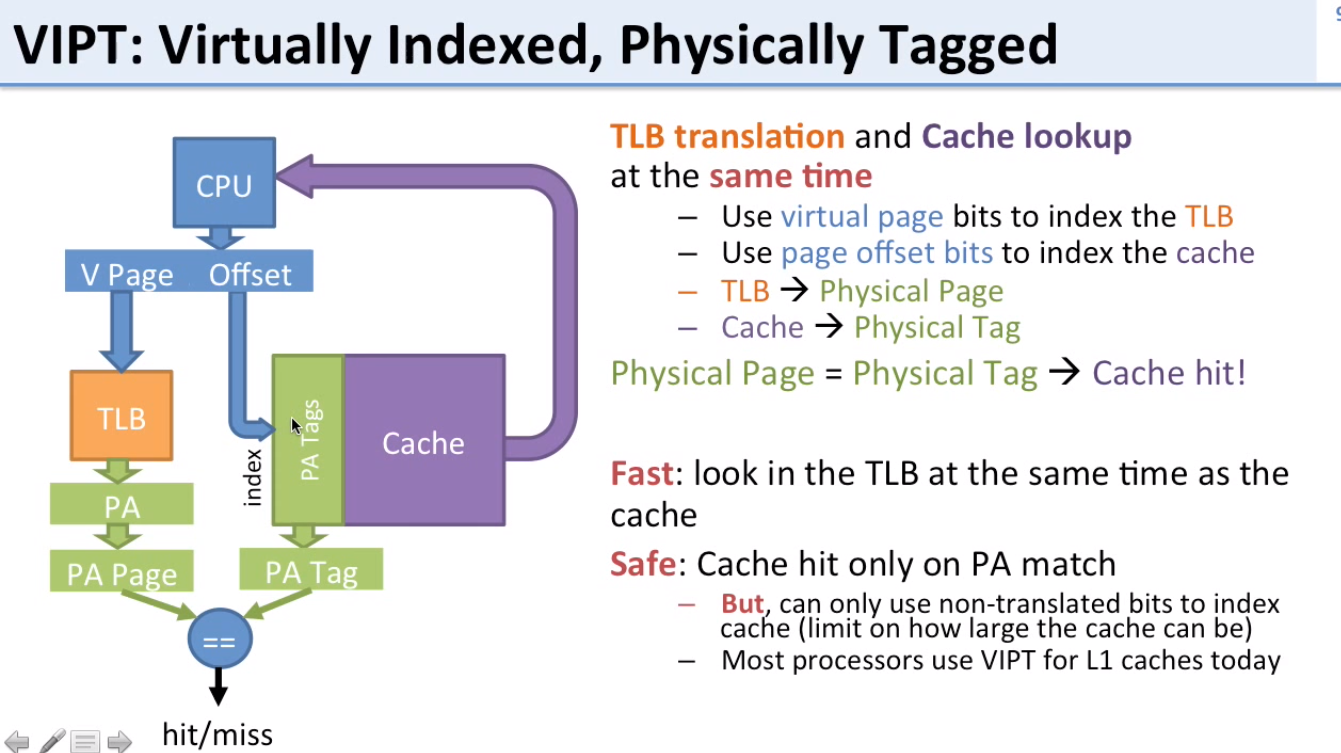

Best of both worlds: VIPT

VIPT: Virtually Indexed, Physically Tagged

- Keeps protection of virtual memory, but allows cache and TLB to be accessed at the same time

- Idea:

- Look up cache with virtual address (index for cache)

- Verify that the data is right with physical tag

- Only get a hit if the tag matches the physical address, but we can start looking for matches with the virtual address

- Notice how the virtual/physical offset is used as an index for the cache, and the virtual page numbers if used to look up in the TLB, allowing for lookup in both the TLB and cache at the same time.

- TLB returns the Physical Page

- Cache returns the Physical Tag

- If Physical Page == Physical Tag, Cache Hit

- Limitation:

- Only offset bits can be used to index cache (limiting the size of the cache)

- Offset bits = 12 bits = 4kB of data

- Thus with 4kB pages, only 4kB bytes can be stored in a directly mapped VIPT cache

- Still used for L1 caches today

Virtual Memory Summary

- Virtual Memory allows

- Mapping memory to disk (“unlimited” memory)

- Keep programs from accessing other program’s memory (Security)

- Fill holes in RAM address space (Efficiency)

- Page Tables

- Used for each program to translate VA to PA

- Use larger pages (4kB) to reduce number of PTE (Page Table entries)

- Fast translation via hardware translation lookaside buffer (TLB)

- TLB + Cache

- Physical cache: Requires translation via TLB first (slow)

- Virtual cache: Uses virtual addresses as index to cache (no translation via TLB needed: fast, but no protection)

- Virtually-Indexed, Physically-Tagged (VIPT) cache: Use VA for index, PA for tag

Linking

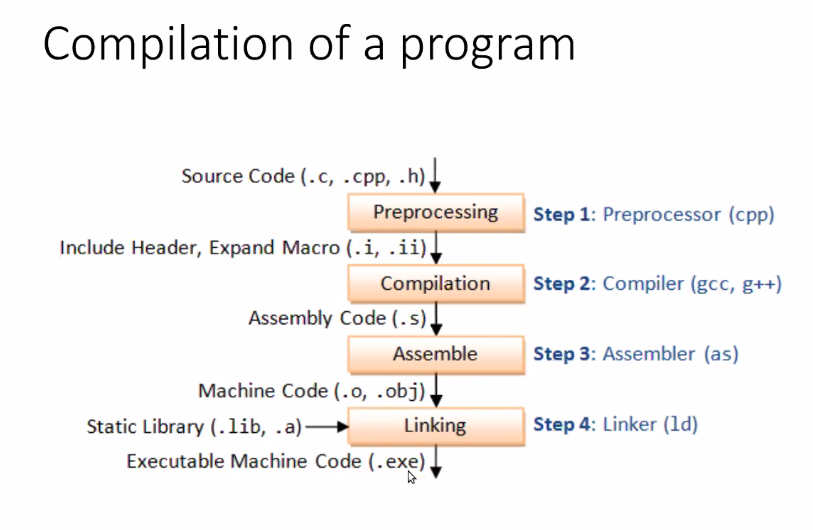

Steps of Compilation

- Preprocessing

- Compilation

- Assemble

- Linking

Static Linking

- Cons:

- Size of file

- Making changes to any of the libraries/linked object files, means you have to relink and recompile the executable every time

Example of static linking

main.c

int add_num(int a, int b);

int main(void) {

printf("%d\n", add_num(1, 2);

}

AddNum.c

#include <stdio.h>

int add_num(int a, int b) {

return a + b;

}

$ gcc -c AddNum.c # Create object file for the file to be linked (AddNum)

$ ar r libStatic.a AddNum.o # Create archive of object files called libStatic.a

$ gcc -o mainStatic main.c libStatic.a # Link object files/archive with compiled main.c

Dynamic File

- Memory address of function is stored instead of the function itself

- Main advantage is that if the linked file is changed, the address of the functions from the linked files in the executable won’t change, so there’s no need to recompile the executable

- Uses shared object files instead of archives like the static linking above

Example of dynamic linking

$ gcc -shared -o libDynamic.so AddNum.c # Create shared object file called libDynamic.so

$ gcc -o mainDynamic main.c -L . -lDynamic # Compile main.c and link the shared object file

You only have to recompile the linked file to create a shared object (.so) to update it.

Static and Dynamic Library Names

- Static Library

- Windows = .lib (library)

- Linux = .a (Archive)

- Dynamic

- Windows .dll (Dynamically Linked Library)

- Linux = .so (Shared object)