Differential Equations with Linear Algebra

Class Description

Textbook: Differential Equation and Linear Algebra by Stephen W. Goode and Scott A. Annin

2.1: Matrix Definitions and Properties

- m x n matrix

- 3 x 4 matrix in the example below

Equality

Matrices

- Same dimensions

Vectors

-

Row Vector: A

-

Column Vector: A

-

The elements of a row or column vector are called the components

-

Denoted via an arrow or in bold:

-

A list of row vectors arranged in a row will always consist of column vectors, and a list of vectors arranged in a column will consist of row vectors

- Example

- Example

Transposition

- Interchange row vectors and column vectors

- Example

Square Matrices

- Square Matrix: An

- Main Diagonal:

- Trace:

- Lower Triangular:

- Upper Triangular:

- Diagonal Matrix:

- Symmetric:

- Skew-Symmetric:

2.2: Matrix Algebra

Matrix Addition

Properties

Scalar Multiplication

- Scalar: Real or complex number

- Scalar Multiplication: If

Properties

- (if

Subtraction

Zero Matrix

- Matrix full of all zeros

- Denoted with just a

Properties

Multiplication

- If

Properties

- Proof

Thus

Identity Matrix

- Example

Kronecker Delta

- A function that gives the values for the identity matrix

Properties of Identity Matrix

- Proof: Use

Properties of Transpose

- Proof

Properties of Triangular Matrices

- The product of two lower triangular matrices is a lower triangular matrix (and the same applies to upper triangular matrices)

The Algebra and Calculus of Matrix Functions

- Matrices can have functions as their elements instead of just scalars

- If

2.3: Systems of Linear Equations

System of Linear Equations

-

System Coefficients:

-

System Constants:

- Scalars

- Correspond to

-

Homogeneous: If

-

Solution: Ordered

-

Solution Set: Set of all solutions to the system

-

If there are two equations with two unknowns, we have two lines, so there can only be the following solutions:

- No solution

- One solution (one intersection point)

- Infinitely many solutions (the lines overlap or are the same)

-

Similarly, with three equations and three unknowns, we have three planes, so there can only be the following solutions

- No solution

- One solution (Three planes intersect at one point)

- Infinitely Many Solutions (the three planes intersect at one line)

- Infinitely Many Solutions (the three planes are the same)

-

All systems can only have one of the three above solution possibilities (no solution, one solution, or infinitely many solutions)

-

Consistent: At least one solution to system

-

Inconsistent: No solution to a system

-

Matrix of Coefficients

-

Augmented Matrix:

Vector Formulation

If we have the following:

The vector formulation:

- Right-Hand Side Vector:

- Vector of Unknowns:

Notation

- The set of all ordered

- For scalar values that are reals:

- Tuples, row vectors, and column vectors are basically interchangeable in this context

Differential Equations

2.4: Row-Echelon Matrices and Elementary Row Operations

- Method for solving a system by reducing a system of equations to a new system with the same solution set, but easier to solve

Row-Echelon Matrix (REF)

Let A be a

- All zero rows of A (if any) are grouped at the bottom

- The leftmost non-zero entry of every non-zero row is 1 (called the leading 1 or pivotal 1)

- The leading 1 of a non-zero row below the first row is to the right of the leading 1 in the row above it

- Values after the leading 1 can be any value

- Pivotal Columns are columns where there is a leading 1

Elementary Row Operations

- Permute row

- Multiply row

- Add the multiple

- The elementary row operations are reversible

Reduced Row Echelon Form (RREF)

- Same as REF but with only 0’s above every leading 1

Rank

- Rank(A) = number of pivotal columns = number of leading 1’s = number of non zero rows in REF form

- Every row equivalent REF has the same rank

- Every RREF of a matrix is the same, but not all row equivalent REF of a matrix are the same

2.5: Gaussian Elimination

-

Gaussian Elimination: To solve a system, use elementary row operations to convert a matrix to REF. Convert matrix back into corresponding equations and solve.

-

Gauss-Jordan Elimination: Convert to RREF and solve.

-

Always either no solution, infinite solutions, or one solution

-

If there is a leading 1 in the last row, there are no solutions since the system is inconsistent

-

Homogeneous:

-

Free variables: Correspond to a non-pivotal column, means there are infinite solutions to system

-

Non-Free variable: Correspond to a pivotal column

Theorem 2.5.9

Let

- If

- If

Corollary 2.5.11

For a homogeneous system, if

Proof

We know

We also know

By Theorem 2.5.9, the system has an infinite amount of solutions

Remark

The inverse is not true. There can still be an infinite amount of solutions if

2.6: The Inverse of a Square Matrix

When

this chapter is about finding what

Potential application of

We can solve for

Theorem 2.6.1

Theorem: There is only one matrix

Proof:

(Uniqueness proof). See these notes

If

- Nonsingular Matrix: Sometimes called invertible

- Singular Matrix: Sometimes called non-invertible or degenerate

Remark:

Theorem 2.6.5

Theorem: If

Proof: Verify that

Thus there is only one solution since we know

Theorem 2.6.6

- This theorem shows when a matrix is invertible and how to efficiently compute the inverse

Theorem: An

Proof:

Let’s prove

Now we prove the converse:

We must show that there exists an

Given

Now we show that

Let

Corollary 2.6.7

Corollary: If

Gauss-Jordan Technique

- Augment the matrix

Properties of the Inverse

If both

Corollary

Theorem 2.6.12

Theorem: Let

Proof

For every

3.4: Summary of Determinants

Formulas for Determinants

-

If

-

If

-

Example

Properties of Determinants

Let

- IF

- If

- If

- For any scalar

- Let

- If

- If two rows (or columns) or

- If

Basic Theoretical Results

- The volume of a parallelepiped is

Theorem 3.2.5

- An

- An

Corollary 3.2.6

An

Adjoint Method

The

Cramer’s Rule

If

4.2: Definition of a Vector Space

- Vector Space: Nonempty set

- Addition

- Multiplication By Scalars

Axioms

- The vector space is closed under both addition and multiplication by scalars

- Commutative

- Associative

Theorem

Let

- The zero vector is unique in

- Every

- If

Function Example

Matrix Example

Polynomial Example

4.3: Subspaces

Subspace: Let

Proposition

Observation

If

Examples

Nullspace

The solution set of a homogeneous system is the nullspace

4.4: Spanning Sets

Let

where

Definition

Given

Observation

Terminology

We can also say

We say

Example

4.5: Linear Dependence and Independence

Minimal Spanning Set

-

Minimal Spanning Set: The smallest set of vectors that spans a vector space

-

A minimal spanning set of

Theorem 4.5.2

If you have a spanning set, you can remove a vector from a spanning set if it is a linear combination of the other vectors and still get a spanning set.

Linear Dependence/Independence

Let

Example

Theorem 4.5.6

A set of vectors (with at least two vectors) is linearly dependent

Proposition 4.5.8

- Any set of vectors with the zero vector is linearly dependent

- Any set of two vectors is linearly dependent if and only if the vectors are proportional

Corollary 4.5.14

Any nonempty, finite set of linearly dependent vectors contains a subset of linearly independent with the same linear span

Proof

By Theorem 4.5.6, there is a vector that is a linear combination of the other vectors. If we delete that, we still have same span. If the resulting subset is linearly independent, then we’re done. If the resulting subset is linearly dependent, then we can repeat the same process of removing the vector that is a linear combination.

Corollary 4.5.17

For a set of vectors

- If

- If

- If

Wronskian

Let

Order matters

Theorem 4.5.23

If

Proof

Suppose the following, for all

If we differentiate, we get the following:

This is a system, and if we get the determinant (Wronskin) to be nonzero, then there is only one solution (trivial) by Theorem 3.2.5

Remarks

- If the Wronskian is zero, we don’t know if the functions are linearly dependent or independent

- The Wronskian only needs to be nonzero at one point for us to conclude that the functions are independent

4.6: Bases and Dimension

Definition

A set

A vector space is called finite dimensional if it admits a finite basis. Otherwise,

Note

All minimal spanning sets form a basis and all bases are minimal spanning sets

Example

Example

Example

Standard Basis: A set of vectors for a vector space where each vector has has zero in all of its components except one

Example

Example

Observation

If

Proof

Since the vectors are linearly independent:

Theorem 4.6.4

If a vector space,

Proof

Let

Let

NTS

Since

There must exist

NTS that

Combine the last two equations:

Rearrange:

We know

This forms an

Corollary 4.6.5

All bases of a finite dimensional vector space have the same number of vectors

Proof

Let there be a basis with

If

Observation

If

Proof

NTS every

In other words, NTS

Now NTS columns of

Definition

If

Convention:

Examples

Corollary 4.6.6

If

Proof

If the spanning set had less than

Theorem 4.6.10

If

Proof

Let

Then the following is true

We know

Every

Theorem 4.6.12

If

Corollary 4.6.14

If

If

6.6: Linear Transformations

Appendix A: Review of Complex Numbers

-

Complex Number: Has a real part and an imaginary part

-

Conjugate: If we have

-

Modulus/Absolute Value:

Complex Valued-Functions

Complex valued functions are of the following form:

- Euler’s Formula

Derivation involves using Maclaurin expansion for

Differentiation of Complex-Valued Functions

where

where

7.1: The Eigenvalue/Eigenvector Problem

-

If

The nontrivial solutions -

A way to formulate this is by interpreting

-

Geometrically, the linear transformation leaves the direction of

Solution to the Problem

According to Corollary 3.2.6, nontrivial solutions exist only when

- Find scalars

- If

- Solve by solving the system

7.2: General Results for Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors

Definition

The Eigenspace

The Eigenspace contains the zero vector

Theorem 7.2.3

- For each

- Algebraic Multiplicity:

- Geometric Multiplicity:

Theorem 7.2.5

Let

Eigenvectors corresponding to distinct eigenvalues are linearly independent

Note 1: By definition of linear independence

Note 2: It is impossible for (non)distinct linearly dependent eigenvectors to correspond to distinct eigenvalues

Note 3: Eigenvectors corresponding to nondistinct eigenvectors can be either linearly independent or linearly dependent

Proof

Proof by induction

Base Case:

Inductive hypothesis: Suppose

Need to show (NTS):

Corollary 7.2.6

Let

. In each eigenspace, choose a set of linearly independent eigenvectors. Then union of linearly independent sets is also linearly independent.

Proof

Proof by contradiction. Assume the union of linearly independent sets is linearly dependent.

Linearly dependence between

Definition

An

Any

Note:

Corollary 7.2.10

If an

Note: if

Proof

Use Theorem 7.2.5

Theorem 7.2.11

For an

or

7.3: Diagonalization

Definition

Let

Theorem 7.3.3

Similar matrices have the same eigenvalues (including multiplicities)

They also have the same characteristic polynomial

Proof

Theorem 7.3.4

An

Proof

First suppose

So

Conversely, suppose

where

A is similar to a diagonal matrix

Definition

A matrix is diagonalizable if it is similar to a diagonal matrix

Solving Systems of Differential Equations

the above can be represented as

where

Let

7.4: An Introduction to the Matrix Exponential Function

If

Properties of the Matrix Exponential Function

- If A and B are

- For all

More results

If

Theorem 7.4.3

If

1.2: Basic Terminology and Ideas

- Definition of Linear Differential Equation

where - The order of the above equation is

- A nonlinear differential equation does not satisfy the above form

Examples of Linear Differential Equations

Order 3

Order 1

Examples of Nonlinear Differential Equations

Both order 2

Solutions to Differential Equations

Definition 1.2.4

A function

Definition 1.2.8

A solution to an

- The solution contains

- All solutions to the differential equation can be obtained by assigning appropriate values to the constants

Not all differential equations have a general solution

Initial-Value Problems

An

where

Theorem 1.2.12

For the initial value problem

if

Example

Prove that the general solution to the differential equation

is

Solution

First, verify that

Then to show that every solution is of that form, use the Theorem that states that there is only one solution to an initial value problem.

Suppose

We can find

Notice that both

Since

1.4: Separable Differential Equations

Definition

A first-order differential equations is called separable if it can be written in the following form

1.6: First Order Linear Differential Equations

Definition

First Order Linear differential equations can be represented as the above forms

Solving the Differential Equation

There can be multiple integrating factors, but we only need one (which means we only need one anti-derivative of

By the product rule

8.1: Linear Differential Equations

The mapping

Note that in general,

Note that

Example

Find

Solution

Example

Find the kernel of

Solution

Finding the kernel of

Use integrating factor to get

Linear Differential Equations

Homogeneous Linear DE’s are of the following form:

Nonhomogeneous Linear DE’s are of the following form:

Theorem 8.1.3

Let

has a unique solution on

Theorem 8.1.4

The set of all solutions to the following

Proof

Rewrite the above as

We know that the kernel of any linear transformation from

Use a proof by induction.

Note: Any set of

General Solution

Example

Find all solutions of the form

Solution

The Wronskian,

Thus the general solution is the following:

Theorem 8.1.6

Let

If

Theorem 8.1.8

Let

for appropriate constants

Proof

Let

If

since

Theorem 8.1.10

If

Proof

8.2: Constant Coefficient Homogeneous Linear Differential Equations

For the differential equation

if

-

-

Auxiliary Polynomial

-

Auxiliary Equation

Theorem 8.2.2

If

- Polynomial differential operators are commutative

- Note: When we write

- Note: The polynomial differential operators commute because polynomials commute!

- Note: You CAN treat the linear transformations as polynomials and multiply them together

Theorem 8.2.4

If

Lemma 8.2.5

Consider the differential operator

Theorem 8.2.6

The differential equation

The above functions also form a basis of

Proof

Using the above lemma, we get

But since

Complex Roots of the Auxiliary Equation

If the roots of the auxiliary equation are complex, then the solutions are

for real valued solutions use Euler’s formula

The are the real-valued solutions to the differential equation

General Result

For the differential equation

- If

- If

Special Case

For the differental equation

the following are solutions

Proof

You can also use the Wronskian to show linear independence (with the vandermont determinant)

So the general solution of the differential equation is

Example

Find the general solution to

Solution

Example

Find the basis of the solution space for

Roots are

Real valued basis

8.3: The Method of Undetermined Coefficients: Annihilators

According to Theorem 8.1.8, the general solution to the non-homogeneous differential equation

is of the form

The previous section showed how to find the solutions to

Insert Part about Annihilators Here

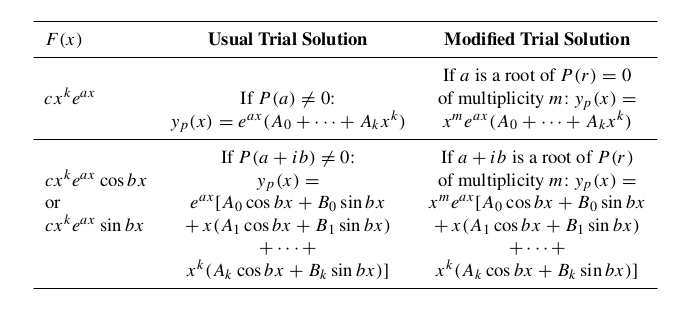

Table

Just use this table here

8.4: Complex-Valued Trial Solutions

Alternative Method for Solving the following constant coefficient differential equation

where

Theorem 8.4.1

If

then

Example

Find the general solution to

Note that

Note that

Since

So

Example

Consider complex version of

Consider homogeneous of above

Find

So

Example

If we wanted to solve the following

we can just use the above

8.6: RLC Circuits

Components of Electric Circuit

- Voltage Source

- Resistor

- Resistance (R) measured in Ohms

- Voltage Drop:

- Resistance (R) measured in Ohms

- Capacitor

- Capacitance (C) measured in Farads (F)

- Voltage Drop:

- Voltage Drop:

- Inductor

- Inductance (L) measured in Henrys (H)

- Voltage Drop:

Representing the Circuit as a DE

Consider a circuit with a voltage source, one resistor, one inductor, and one capacitor

The above is a 2nd order linear differential equation with constant coefficients.

If

-

Underdamped if

-

Critically Damped if

-

Overdamped if

In all three cases,

So after some time,

9.1: First-Order Linear Systems

A system of differential equations of the form is called a first-order linear system

where

If

Note that any

Example

Convert the following system of differential equations to a first-order system

Let

9.2: Vector Formulation

The following first-order system

can be written as follows

Let

Theorem 9.2.1

Definition 9.2.2

If

then the Wronskian

Theorem 9.2.4

If

Example

Show that

9.3: General Results for First-Order Linear Differential Systems

Theorem 9.3.1

Let

The initial value problem

Homogeneous Vector Differential Equations

Theorem 9.3.2

Let

- Any set of

- The corresponding matrix

- The fundamental solution set is just a basis of the solution space of

Theorem 9.3.4

Let

at every point in

- This means to see if

- The general solution to

Proof

Show the contrapositive: If

If

Then there exists

Let

We know that

But not all

Example

Verify that

Solution

- Find

- Then use the Wronksian to show that the wronskian is never zero, so

Nonhomogeneous Vector Differential Equations

Let

on

9.4: Vector Differential Equations: Nondefective Coefficient Matrix

Theorem

If

Let

Proof

Since

where

Let

Example

Find a fundamental set of solutions of

Solution

Roots:

General Solution:

Fundamental Set: