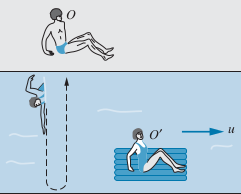

notes college physics special relativity statistical physics quantum mechanics photoelectric effect compton scattering rutherford waves solid state statistical physics nuclear physics

f601fce @ 2022-12-20

7344 Words

Introduction to Modern Physics

Class Information

The course will provide an introduction to the special theory of relativity and quantum mechanics, with emphasis of their applications to atomic, molecular and solid state physics. The course is calculus based and writing intensive; it relies heavily on problem solving and technical writing.

Textbook: Modern Physics by Kenneth Krane

2: Special Relativity

Galilean Transforms

- Galilean Relativity: Also known as classical relativity. Describes how two inertial (non accelerating) reference frames see the same event (turns out to not work in all cases).

- Transforms: Allows you to convert from one coordinate frame to another

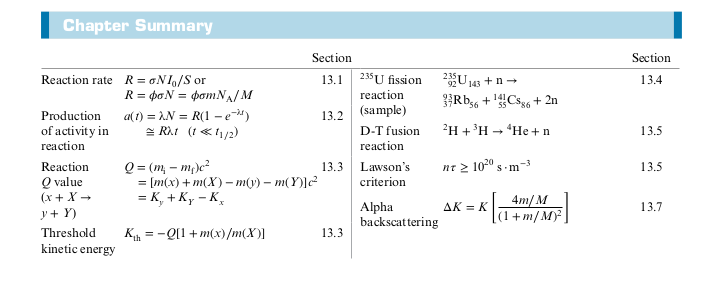

- Suppose we have two coordinate frames,

One of the postulates in Galilean Relativity, is that time is the same for all observers

Visual depiction of where the

Taking the derivatives with respect to time yields (note ' does not denote derivative in this case):

- Note Newton’s Laws hold in these reference frames, since acceleration are measured to be the same (as long as

- Note

Example 2.3

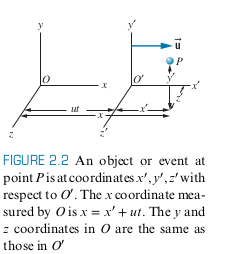

Suppose a swimmer always swims with velocity

Upstream and Downstream Case

Upstream

- Note that

- Since

- The total time to go Upstream a length

- Note that we use

Downstream

- Note that

Calculating Time to go Upstream and then Downstream

- Just add time from upstream and downstream

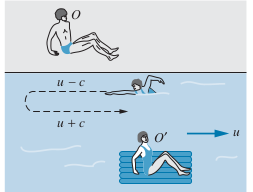

Cross-stream Case

We want the swimmer to swim directly across the river bank in a straight line, perpendicular from the river bank, according to observer

- Note that

- Note that the speed of the swimmer relative to the water is always

Michelson-Morley Experiment

-

Old physicists thought light had to travel in medium

- This implies preferred reference frame existed (the reference frame O’ that moved at the same speed as the medium)

- This also implied another reference frame moving at a different speed relative to the medium would have a different speed of light

-

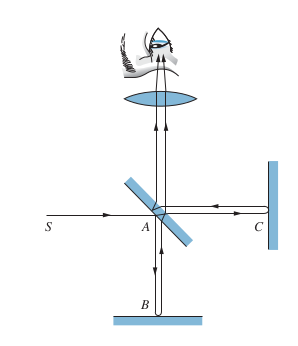

Mirror B is half silvered (some light gets reflected while some goes through), so light travels 2 separate paths, namely AB and AC

-

There is a phase difference between the two light beams, which can be measured by looking at how many fringes appear due to interference. The phase difference is due to the following

- Difference in path length for AB and AC

- Speed of earth through ether (medium that light supposedly travels through)

-

Michelson and Morely didn’t care about 1. and wanted to measure 2. since they were trying to measure the ether

-

This is similar to Example 2.3, with

-

In order to isolate 2, they rotated the apparatus 90 degrees.

- Phase difference due to difference between AB and AC doesn’t change, since path difference doesn’t change

- But phase difference should occur due to cross-stream becoming upstream and vice versa

-

Count how many fringes change from bright to dark to see how the phase difference changes

-

Each time the fringes change, that represents a time difference between the paths due solely to movement relative to the ether and not due to the difference in path lengths of AB and AC

-

See textbook and Wikipedia for more details

Einstein’s Postulates

- The laws of physics are the same in all inertial reference frames

- The speed of light in free space has the same value in all inertial reference frames

Time Dilation and Length Contraction

- Time Dilation: Observer

- Length Contraction: Observer

- Proper Length

- Proper time

- Time dilation in one frame of reference can be seen as length contraction in another reference frame.

Simultaneity

From an observer

Twin Paradox

Imagine Twin1 is on earth and Twin2 departs on a spaceship. From Twin1’s perspective, Twin2 is moving away with velocity

Example

Twin1 stays on earth and Twin2 departs on spaceship at age 0. Twin2 travels at

- According to Twin1, it takes 6 ly/0.6c = 10 years to reach the planet and another 10 to return to earth

- According to Twin2, the length of 6 ly is contracted by a factor of

- Since the length has been contracted for Twin2, Twin2 will measure 8 years to go to the planet and another 8 to return

- Imagine Twin1 sends a light pulse every year during the whole trip (20 years according to Twin1, 16 according to Twin2).

- The frequency at which Twin1 sends the light pulse is dopper shifted

On the journey to the planet, Twin2 will receive pulses at a frequency of

And on the journey back to earth, Twin2 will receive pulses at a frequency of

- So according to Twin2, during the 16 year journey, Twin2 receives 20 pulses, meaning Twin2 aged less

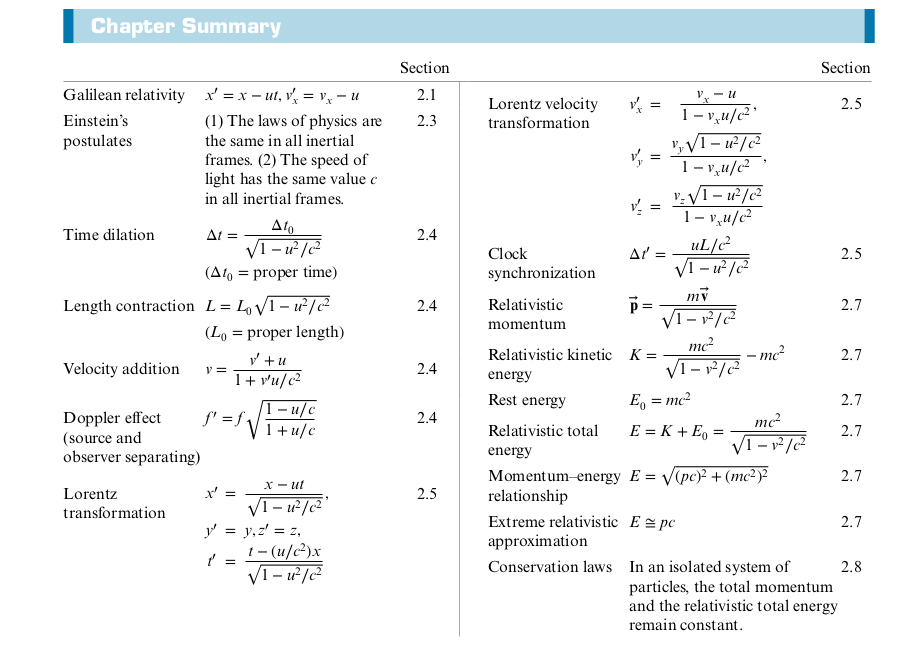

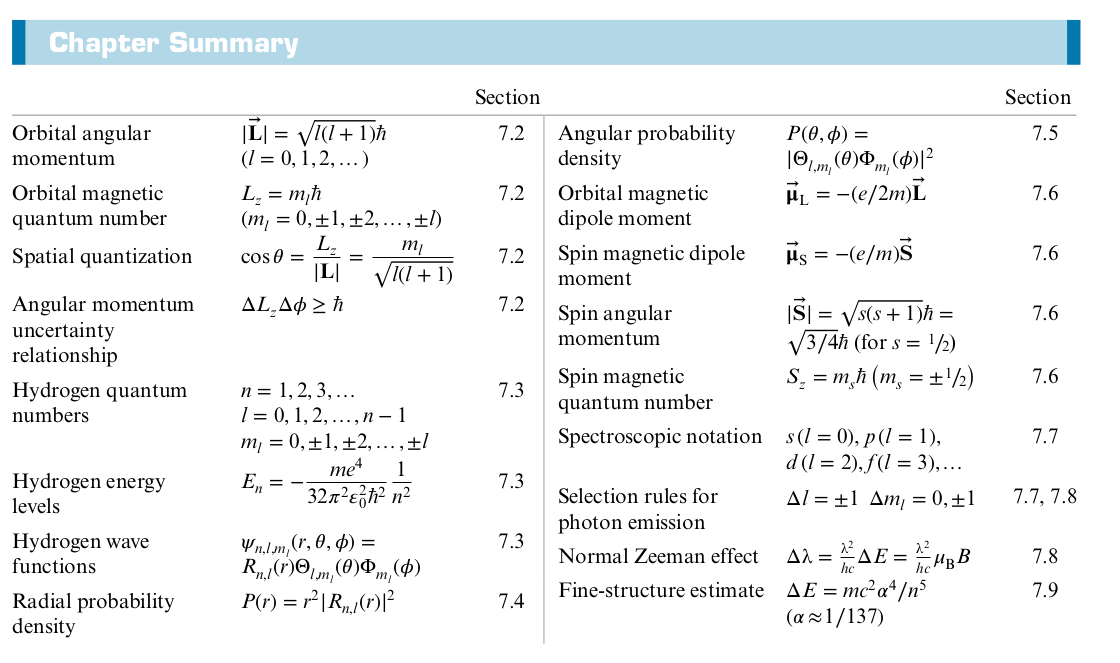

Chapter 2 Summary

Derivation in textbook:

3: Particle-Like Properties of Electromagnetic Radiation

Review of Electromagnetic Waves

- Wave Number,

- Angular Frequency (

- Pointing Vector, shows direction the EM wave propagates

- Note the following

- Intensity fluctuates with time with frequency

Diffraction

Crystal Diffraction of X Rays

-

Diffraction Grating: Device with many slits that allow us to observe interference patterns

- Superior resolution - allows separation of wavelengths close to one another

- Reasonable values of

- Reasonable values of

- Superior resolution - allows separation of wavelengths close to one another

-

Maxima corresponding to different wavelengths appear at different angles

X Ray Diffraction needs light on the order of

- This means the grating spacing has to be less than

- The spacing between atoms in most materials is around this value

- Use the atoms in materials as diffraction grating!

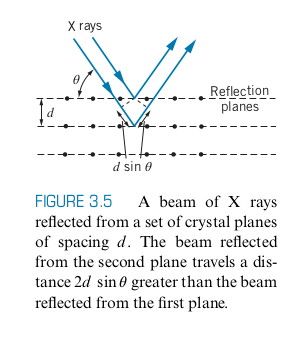

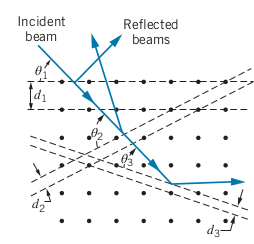

Bragg’s Law

-

Here

-

Instead of using x-ray diffraction to separate different wavelengths, we use X-Ray diffraction to see the spacing between the planes inside materials

-

We use more than one wavelength to get more

The Photoelectric Effect

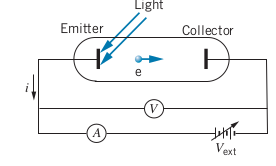

- Photoelectric effect: When a metal surface is illuminated with light, it emits electrons, called photoelectrons

-

The maximum

-

The stopping voltage is determined by incrementally turning up

-

The work function (

Classic Theory of Photoelectric Effect

Classical wave theory predicts the following

- The Photoelectric effect should occur at any frequency and wavelength since according to wave theory, only the intensity of the light matters

- The first electrons should be emitted in a time interval of the order of seconds after the radiation strikes the surface

- The time interval

Experimental results of photoelectric effect

- For a fixed wavelength, the

- Doubling intensity yields no change in stopping voltage, which means the

- The photoelectric effect does not occur at all if below a certain frequency

- The first photoelectrons are emitted in the order of nanoseconds

- Above results show wave theory is not enough to account for photoelectric effect

Quantum Theory of the Photoelectric Effect

-

Einstein proposed that the energy of EM radiation is not continuously distributed over the wavefront, but rather in discrete packets called photons

-

Energy of a photon

-

Einstein believed the entire energy of the photon is delivered instantaneously to a single photoelectron

- Explains why only certain frequencies work for photoelectric effect

- Explains why release of photoelectron is nearly instantaneous

-

Photoelectron is only released when the photon energy

-

Intensity doesn’t appear in the above

- For a fixed frequency, doubling the intensity means twice as many photons strike the surface and twice as many photoelectrons are released, but each photon has the same

- For a fixed frequency, doubling the intensity means twice as many photons strike the surface and twice as many photoelectrons are released, but each photon has the same

-

Experiments by Millikan using the photoelectric effect were able to obtain

-

Note: The value

Thermal Radiation

- Another phenomena that can’t be explained by classical wave theory

- Every object radiates thermal radiation with intensity

Stefan’s Law

Wien’s Displacement Law

-

The

-

Blackbody: Perfect emitter and absorber of radiation

- Whitebody Reflects all incoming radiation perfectly

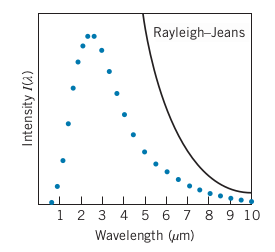

Classical Theory of Thermal Radiation

Rayleigh-Jeans Formula: Intensity per unit wavelength interval

-

Works for long wavelengths, but fails miserably for shorter wavelengths, dubbed the ultraviolet catastrophe

-

Problem for classical physics, since E&M and Thermo, which the Rayleigh-Jeans formula was derived from, have been tested and found to be accurate, but fail for this case

Quantum Theory of Thermal Radiation

- Max Planck developed a theory where each oscillator can emit and absorb energy in discrete quantities that are integer multiples of a basic quantity of energy,

This leads to a revised formula for the intensity of radiation (derivation in textbook)

- By Stefan’s Law, the following relationship between the Stefan-Boltzmann Constant and Planck’s constant can be derived

- Using the known value of the Stefan-Boltzmann Constant and intensity data in 1900, Planck was able to calculate the value of

- 15 years later, Millikan arrived at a similar value of

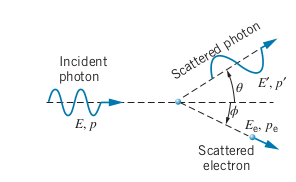

The Compton Effect

-

Another way for radiation to interact with matter

-

Radiation hits electron and leads to the incoming photon and electron being scattered

-

More proof that photon exists, since the interaction implies a photon is a particle with momentum

- Compton wavelength of the Electron: Not a true wavelength but a change of wavelength

Bremsstrahlung

When an electron is accelerated by a potential difference

An electron can hit a target and slow down, and in doing so, release the energy as bremsstrahlung (braking radiation)

In general, the energy of the photon emitted when the electron deaccelerates:

If the electron stops completely (at rest)

4: The Wavelike Properties of Particles

De Broglie

By this point in time, scientists knew that light had wavelike properties and had the wave-particle duality. But it was unclear whether this was only for light or whether matter could exhibit wavelike phenomena.

They knew

De Broglie hypothesized that matter can exhibit wavelike properties.

- Experimental evidence like diffraction of electrons and neutrons through solids, showed that matter could actually exhibit wavelike properties

Heisenberg Uncertainty Relationships

6: The Rutherford-Bohr Model of the Atom

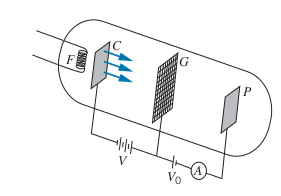

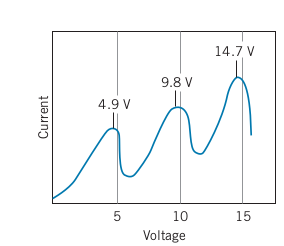

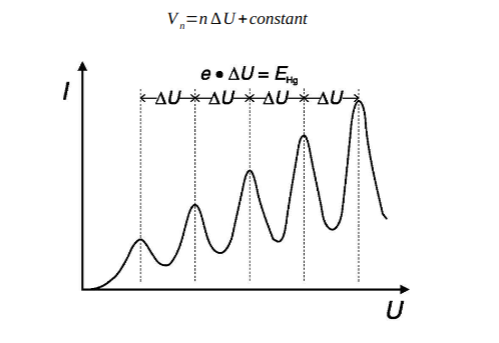

Franck-Hertz Experiment

-

Direct evidence that electrons in atoms can exist in discrete excited states

The Filament,

- As

- Then at a certain

- Repeat 1. and 2.

-

Every time there is a drop in current, the voltage at the peak current is a multiple of 4.9

-

Also note that the distance between the peaks is 4.9

-

Rutherford Scattering Experiment

Juicy derivation in textbook

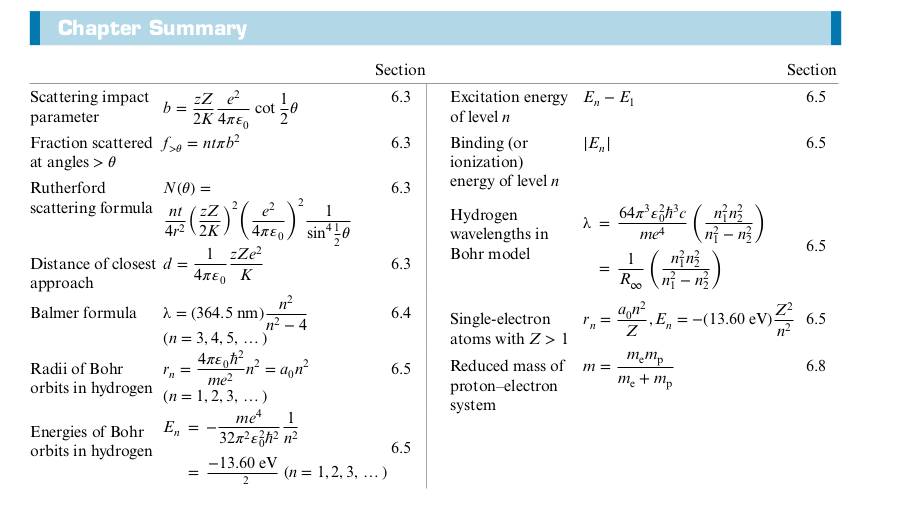

Summary

5: The Schrödinger Equation

Schrödinger Equation describes the electron (or any other quantum state) as a wave. Using the wave function, we can find the average momentum, average position, and the probability of finding the particle in certain positions.

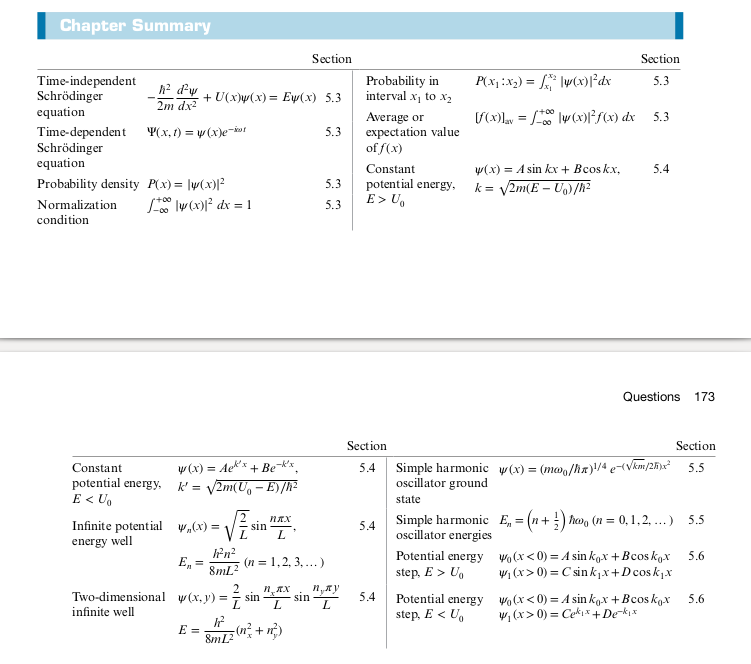

Summary

Two-Dimensional Quantum Oscillator

- Note that if there are two ways for

- There are three ways for

- The number of ways for a system to be at a certain energy is called the degeneracy

- Degeneracy arises from more than one quantum number

- The number of quantum numbers describing a system is equal to the number of dimensions (e.g. 2 quantum numbers for 2D problem)

- Degeneracy gives rise to a lot of the properties and structure of atoms

7. The Hydrogen Atom In Wave Mechanics

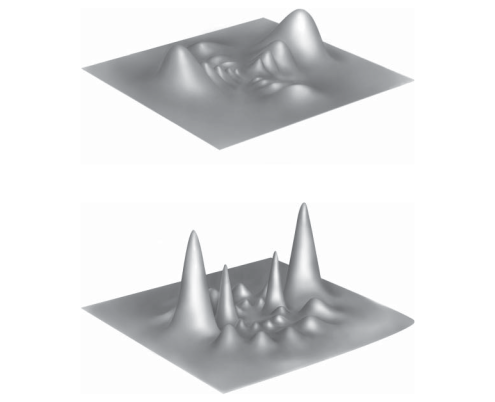

Above shows the probability of finding an electron in

Deficiencies in Bohr-Rutherford Model

- Looking at spectral lines showed two streaks close to each other, not addressed by Bohr Model

- Later found to be due to intrinsic spin of electron

- The Bohr Model has the electron in an orbit around the nucleus at a fixed radius

One Dimensional Atom

We can use the Schrödinger Equation to solve the above Coloumb potential in one dimension

A trial solution for the above differential equation:

Substituting the trial solution gives

where

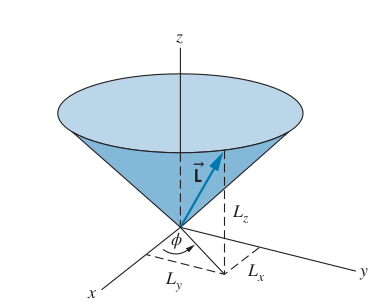

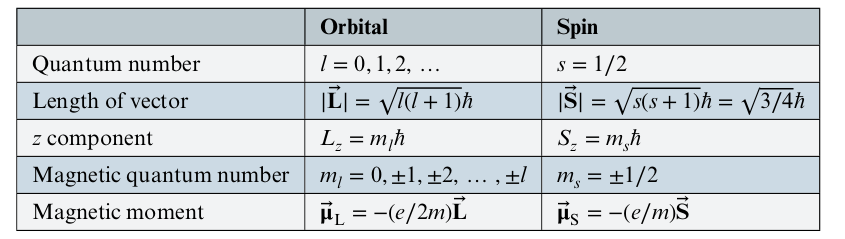

Angular Momentum in the Hydrogen Atom

-

Bohr’s model treated angular momentum as quantized, with the angular momentum of an electron as

-

But the quantum version of angular momentum

-

-

We can only know at most one component of

-

If we know

Graphical Representation of the uncertainty for angular momentum

The Hydrogen Atom Wave Function

We can represent the wave function in 3D in spherical coordinates

The potential energy only depends on

- Radial Function

- Polar Function

- Azimuthal Function

Each function is a function of a single variable

Quantum Numbers

Since the hydrogen wave function is 3D, we have 3 quantum numbers:

Recall that

* At

* At

* At

* In general, at energy

- You can find the probability density by integrating

Intrinsic Spin (Stern-Gerlach Experiment)

An orbiting electron creates a magnetic dipole moment in an external magnetic field, which allow counting

-

The Stern-Gerlach experiment had a non-uniform magnetic field cause an uneven force applied to the incoming atoms to move to one direction or another

- The atoms went to specific spots on the target screen, showing quantization

- Three spots, center (no deflection, up, and down)

- However each of these three spots was actually composed of two more sub subspots, indicating the electron itself also had a spin

- Electron’s intrinsic spin arises from relativistic effects

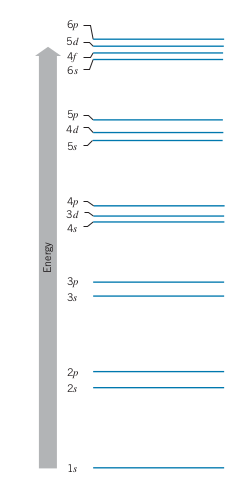

Energy Levels and Spectroscopic Notation

Selection Rule

When an electron loses energy and goes to a lower state, the selection rule shows the most probable transitions, obtained by solving Schrödinger’s equation and computing transition probabilities

Examples:

- 3s cannot emit photon in 2s (

- 3p can go to 2s or 1s, but not

Summary

8: Many-Electron Atoms

- Orbit of earth around sun

- Simplify by only considering two body problem

- Good approximation since other planet’s gravity is miniscule compared to sun’s

- Electrons and Nucleus

- Can’t approximate like in the above problem when dealing with more than one electron around the nucleus

- Each electron exerts a force on every other electron around the nucleus

- This force is significant, so you can’t just correct for it and only consider the force from nucleus

- Example of Many-body problem, with 3 or more particles mutually interacting with each other

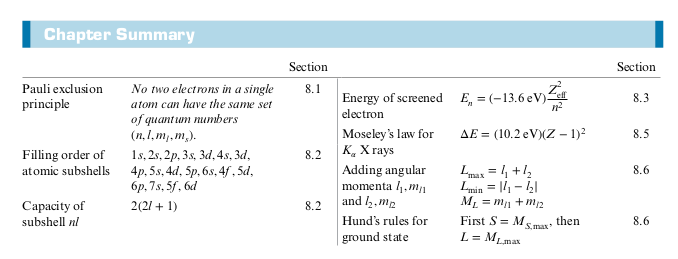

Pauli Exclusion Principle

- We might think that all the electrons will occupy the lowest energy level, which is the 1s state

- But if this were true, the properties of atoms would vary smoothly

- Most properties of different elements don’t vary smoothly, with the exception of the energy of x-rays emitted by atoms

- But if this were true, the properties of atoms would vary smoothly

- Pauli Exclusion Principle: No two electrons in a single atom can have the same set of quantum numbers (

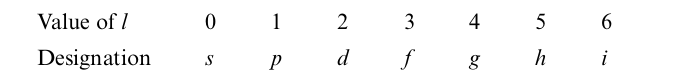

Electronic Structure of Many-Electron Atoms

- Electrons in the same shell (same

- Subshells: Specific combinations of

- E.g. 3s, 4p, 3d, 2s, etc.

- Total number of electrons with in a subshell is

- 2 factor comes from two spin

- 2 factor comes from two spin

Outer Electrons: Screening and Optical Transitions

- Electron Screening: Electrons in the outer levels experience less of the charge from the nuclues due to the repulsive forces from the electrson in inner shells. Thus the effective charged experienced by the outer electrons is less

Inner Electrons: Absorption Edges and X-Rays

-

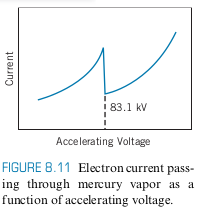

If we repeat the Franck Hertz Experiment but with tens of kV instead of tens of volts, we can knock out the inner electrons instead of the outer electrons

-

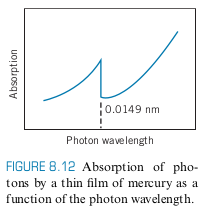

We get the following graph if we perform FH experiment on Hg with kV

- 83.1 kV corresponds to 0.0149 nm, which is in the X-ray region

- 83.1 kV corresponds to 0.0149 nm, which is in the X-ray region

-

If we bombard a thin film of mercury with x-rays, we see the absorption drops at 0.0149 nm (photoelectric effect), in agreement with above experiment

- Absorption Edge: Sudden drop in current or absorption

- Absorption Edge: Sudden drop in current or absorption

-

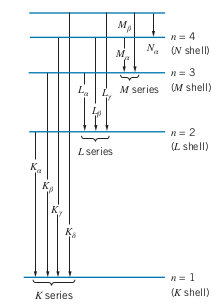

K corresponds to

X-Ray Transitions

- We showed previously, that one way to produce x-rays is through Bremsstrahlung by accelerating electrons and then slowing them down

- This produces a continous x-ray spectrum

- One way to produce discrete x-ray spectrum is by allowing an inner electron to move down to a lower energy level

- E.g. knock out 1s electron. This leaves vacancy in K shell, so another electron from another shell

- If an electron from the

- If an electron from the

- E.g. knock out 1s electron. This leaves vacancy in K shell, so another electron from another shell

Moseley’s Law

The energy for a

Chapter 8 Summary

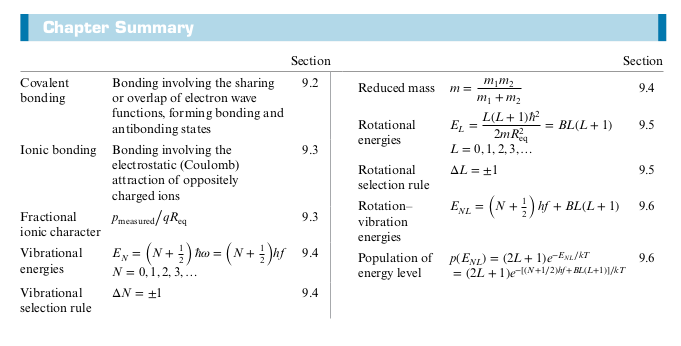

9: Molecular Structure

Chapter 9 Summary

10: Statistical Mechanics

- Some experiments can be described by looking at single isolated events

- Rutherford Scattering

- Compton Scattering

- But for many phenomena, you have to analyze the average behavior using statistics

- Classical Statistics

- Quantum Statistics

Statistical Analysis

- Microscopic properties

- Velocity and Position of every single atom

- Not practical for even a small system containing

- Macroscopic properties

- Temperature and pressure of a gas

- Relationship between microscopic and macoscopic properties

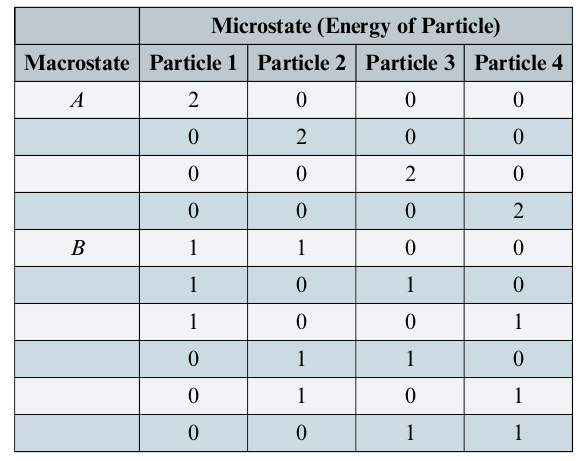

Macro/Micro state Example

Consider a system with 4 particles with a maximum allowed energy of 2 units of energy

- Macrostate

- A: Only one particles has 2E

- B: Two particles have 2E

- Microstate

- Total of 10 microstates (with 40 particles total)

- The number of microstates for a particular macrostate is called the multiplicity and denoted with

- All microstates of a system are equally probable

- E.g. In this example, the probability of finding a system in macrostate B 60% of the time

- Probability of finidng a particle with 2E is 4/40 = 10%

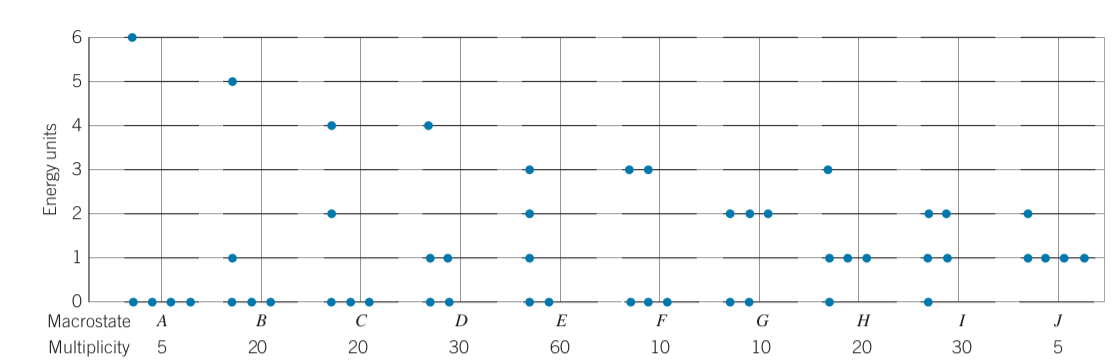

Classical and Quantum Statistics

Consider a system with 6 units of energy total and with 5 identical particles

-

Multiplicity of each macrostate (Number of microstates per macrostate):

- Where

- Where

-

Total number of microstates for

-

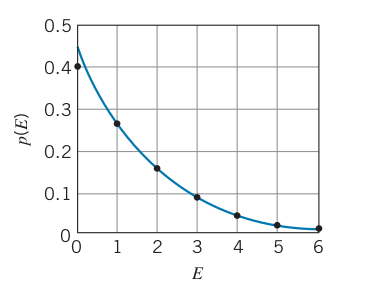

Probability of finding a particle with energy,

- Where

- Where

- The curve shows

- Some other phenomena do not behave as well with classical physics such as electric conductivity, heap capacity

Quantum Statistics

- Quantum particles must be treated as indistinguisable

- Multiplicity of each macrostate is 1

- Quantum mechanics imposes limits on max number of particles in a given state

- E.g. electrons have spin up or down, no two electrons in the same state

The Density of States

-

Distribution Function:

-

Our ultimate goal is to find a function that gives us the number of particles at energy

- This quantity depends on

- The number of states available at energy

- Example: For dilute hydrogen gas, the number of states available at each energy level,

- Example: For a molecule with rotational excited states like HCL, the number of states available at each energy level,

- Example: For dilute hydrogen gas, the number of states available at each energy level,

- The number of states available at energy

- This quantity depends on

-

Thus we have the following expression for the number of particles at a given

- where

- where

-

-

For large systems, we can’t keep track of every individual particle and separate out each individual state, so we look at the number of states in a small interval

- treats

- treats

-

The Density of States

-

The number of populated states,

-

Density of States of Gas of Particles (Electrons or Molecules)

where

- Derivation in textbook

Density of States in a Gas of Photons

- Derivation in textbook

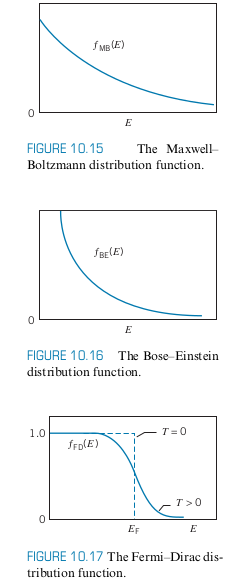

Quantum Statistics

-

Particles that don’t obey Pauli Exclusion principle have integer spins

- Their properties are determined by the Bose-Einstein Distribution Function

- where

- where

- Their properties are determined by the Bose-Einstein Distribution Function

-

Particles that do obey Pauli Exclusion principle have half integer spins

- Their properties are determined by the Fermi-Dirac Distribution Function

- where

- where

- Their properties are determined by the Fermi-Dirac Distribution Function

-

Suppose the normalization constants are

-

For small

-

For small

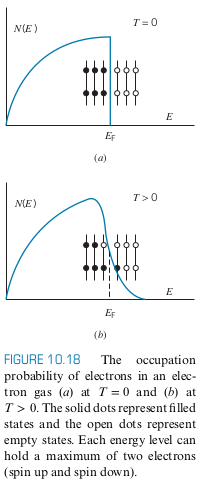

- Consider a gas of electrons with

- The figure below shows a possible configuration of electrons

- Notice that only the states near

Limits of Classical Statistics

-

Quantum behaviour can be neglected when

-

Thus we can still use classical statistics whenever

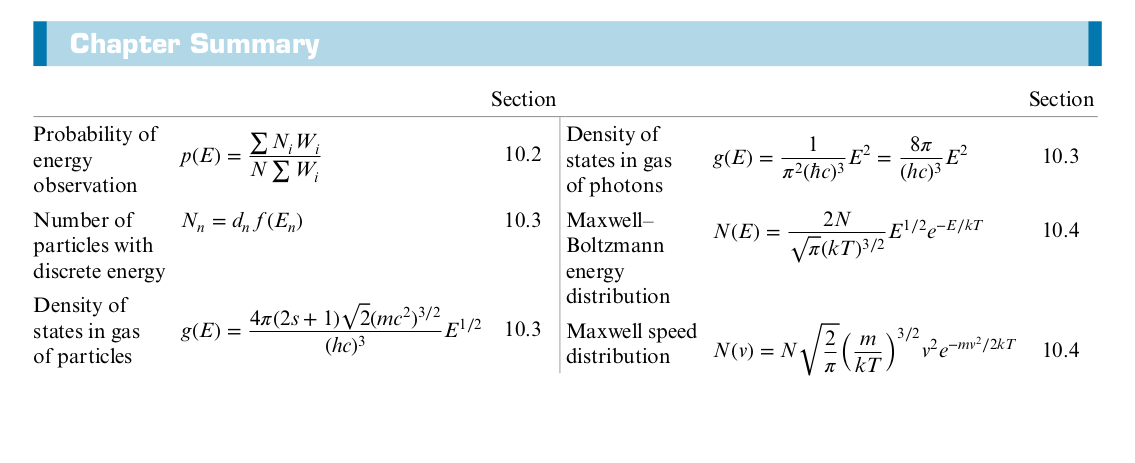

Chapter 10 Summary

11: Solid State Physics

- Properties of solids based on quantum mechanical interactions

- Solid State Physics is often called Condensed Matter Physics nowadays

Crystal Structures

- Crystal: Atoms/Molecules occupy places in a latice at periodic intervals

- Salt, Metals, etc.

- Long-Range order: We can determine how the crystal looks by looking at a local arrangement of molecules/atoms, due to the repeating nature of the lattice

- Amorphous Solid: No repeating pattern/structure

- Glass, Paper

Ionic Solid

-

Coulomb Force

-

Cubic Lattice

-

Face Centered Cubic (FCC)

-

Body Centered Cubic (BCC)

-

Adding up the individual Coulomb potential energies from every other atom yields a convergent infinite series

Covalent Solid

Metalic Solid

- D orbitals form a “sea of electrons” (Fermi-Gas)

Molecular Solid

- Depends on Dipole Bonds (e.g. hydrogen bonds)

- Note how much weaker bonds in molecular solids are

- Coulomb force

- Dipole

- Coulomb force

Heat Capacity of Solids

Classical thermodynamics

- The equipartiaion theorem states each degree of freedom has

- 6 degrees of freedom for particle in a lattice

- Expect there to be

- Heat Capacity,

- This would mean that the heat capacity for all solids is the same at all temperatures

- Result is known as Law of Dulong and Petit

- Works well at room temperature, but not as temperature is decreased

- Result is known as Law of Dulong and Petit

Apply Quantum Statistics

- Assume heat capacity is due to electrons in metal (Fermi Gas)

We get the following result

- The above results predicts that the graph of

- Copper’s heat capacity at

Einstein’s Theory

- Assumed oscillations of the solid (not atom) obey Bose-Einstein statistics

- EM quanta (i.e. photons) obey Bose-Einstein statistics

- Similarly, phonons quanta of vibrational energy obey Bose-Einstein stats

- Assume that all phonons have same vibrational frequency

Quantized oscillator

Boson gas

-

-

Peter Debye: Then expanded on above, and assumed phonons have a continous spectrum of frequencies (like photons) instead of discrete frequencies

-

-

The total heat capacity is a combination of the Bosonic lattice vibrations and the Fermic Gas electron contributions

-

The

Electrons in Metals

Electrons can be treated as fermi gas

- Even though the Fermi energy depends on temperature, we can assume it is constant for a material since the Fermi energy at 0K and room temperature is pretty much the same

Electric Conduction

where

- Assume current is constant in conductor

- When electrons are accelerated by

- Electrons acquire on average a drift velocity

- When electrons are accelerated by

- We also have

- Combinbing gives

For a classical particle

- If we take

Quantum Theory of Electrical Conduction

- Treating the electrons as a fermi gas instead of a classical particle with velocity

- Thus that means our

- A perfect lattice means the mean free path is infinite and thus

- A perfect lattice means a infinite conductivity

- A perfect lattice means the mean free path is infinite and thus

- In a real metal lattice, the following contribute to electron scattering

- Atoms are in random thermal motion, so the lattice is not always perfect

- Dominates at high temperatures, depends on

- Dominates at high temperatures, depends on

- Lattice imperfections/impurities

- Dominates at lower temperatures, independent of

- Dominates at lower temperatures, independent of

- For thermal motion: Average vibrational potential energy is proportional to

- Thermal conductivity behaves in almost the same way as electrical conductivity

- The ratio of thermal conductivity and electrical conductivity is independent of material, but depends on temperature, since

- Wiedemann-Franz Law

where- Not always correct since it assumes

- Not always correct since it assumes

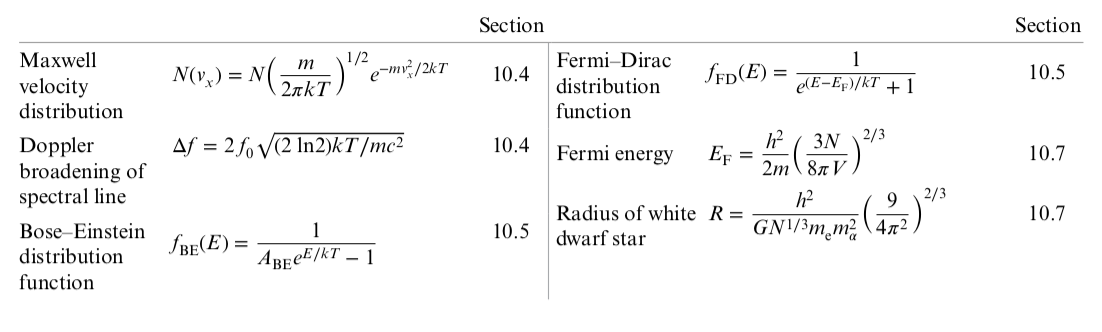

Band Theory of Solids

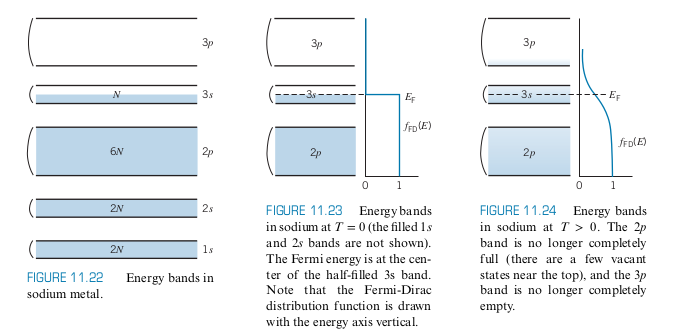

- Consider Sodium with a half-filled 3s subshell

- When we move more an more sodium atoms together, the wavefunctions overlap. When we have a very large number

- Each band can hold

- Each band can hold

-

Notice that

- 3s is the conduction band

- Even a small potential (~1V), electrons can absorb energy since there are

-

At the ground state, Sodium’s 3s band holds

-

Consider all the other bands in sodium

-

Conductors have the Fermi level halfway within a band

- There are

- There are

-

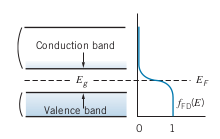

Insulators have the Fermi level halfway between two different bands (See below) and a large gap with

- Even when the FD distribution spreads out when

- Even though there are a large number of electrons in the valence band for electrical conduction, there are not many unoccupied states they can move to, so there is no way they contribute to conduction

- Although the conduction band has lots of empty states, there are almost no electrons in the conduction band to contribute

- Even when the FD distribution spreads out when

-

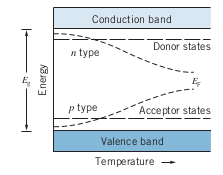

Semiconductor: Similar band structure as insulators, but with the gap energy at around

- A small population of electrons can occupy a bit of the conduction band

- Below is an example of the band structure at room temperature. Note the lighter blue indicates that there are a few electrons in the conduction band with lots of unoccupied states to move to, and there are a lot of electrons in the valence band with a few unoccupied states to move to as well, which both contribute to a bit ofconduction

- The conductivity of semiconductors also depends more on the temperature as well, since increasing temperature spreads out the

- Doping, which involves introducing small amounts of impurities, can also move the

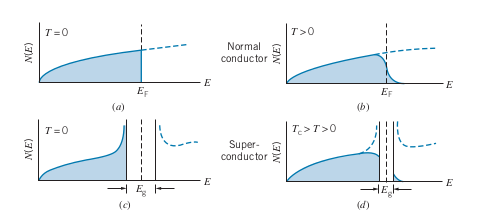

Superconductivity

-

For an ordinary conductor, as

-

However, for a supercondcutor, the resistance rapidly goes to 0 below a certain

-

BCS theory states that as temperature is decreased for a superconductor, there is an energy gap,

- At and below

- The energy gap represents the binding energy of the cooper pairs

- At and below

Intrinsic and Impurity Semiconductors

-

-

There is one atom in

-

Thus if there are

-

Holes exist in the valence band if some electrons are in the conduction band

- Conduction in an intrinsic semiconductor is due to the electrons moving in the conduction band and also due to the positively charged holes “moving”

- Electrons move more easily, so contribute more than holes to conduction

-

Doping creates impurity semiconductors

- N-Type: Uses Donor atoms that donate electrons to the conduction band

- Phosphorus, arsenic, etc.

- P-Type: Uses acceptor atoms that add holes to the valence band

- Boron, Gallium, etc.

- Adding donors or acceptors creates new energy bands/states

- At

- As

- N-Type: Uses Donor atoms that donate electrons to the conduction band

Semiconductor Devices

Diode

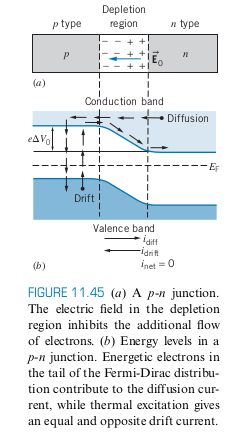

- When a P-type semiconductor and N-Type semiconductor are placed in contact with one another, electrons move from the n-type to the p-type

- In the middle of the two is the depletion region, where charge carriers are somewhat depleted, since the holes are already filled with electrons from the n-type

- Excess electrons that have filled holes in p-type give it a negative charge and the lack of electrons in the n-type give it a positive charge

- At equilibrium, there is enough negative charge in the p region to repel more electrons. At equilibrium,

- At equilibrium there is a potential

- Drift Current and Diffusion Current: equal at equilibrium

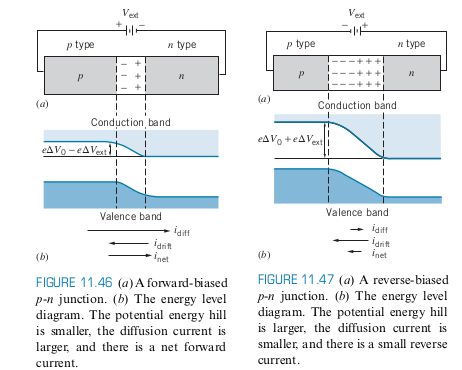

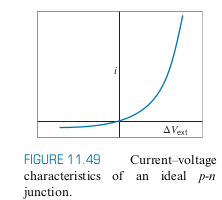

- When you apply a voltage, the energy barrier is raised or lowered, and affects the drift and diffusion currents, so that they are no longer equal

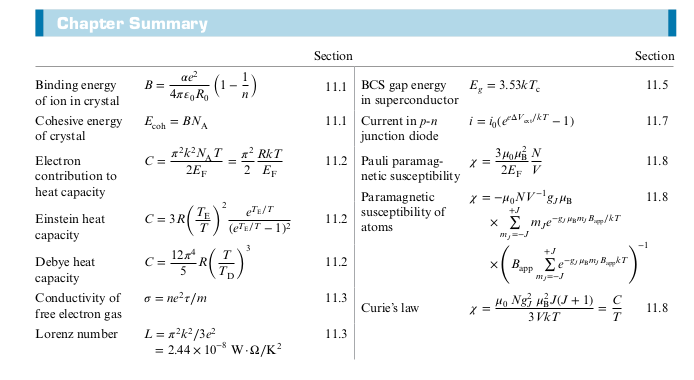

- Reverse Bias: Causes very little current to flow

- Forward Bias: Causes a significant amount of current to flow

- Note how current basically only flows through one way: Diode

Photodiode

- External current excites electron from valence to conduction, when the electron drops, light is emitted

- Note that the energy gap is on the order of

- Note that the energy gap is on the order of

- Running the photodiode in reverse can be used to count photons or used as a solar cell type thing

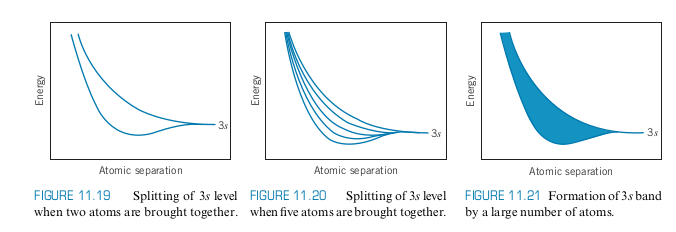

Chapter 11 Summary

12: Nuclear Structure and Radioactivity

Nuclear Constituents

Nuclear Size and Shape

Nuclear Mass and Binding Energies

The Nuclear Force

Quantum States in Nuclei

Radioactive Decay

Alpha Decay

Beta Decay

Gamma Decay and Nuclear Excited States

Natural Radioactivity

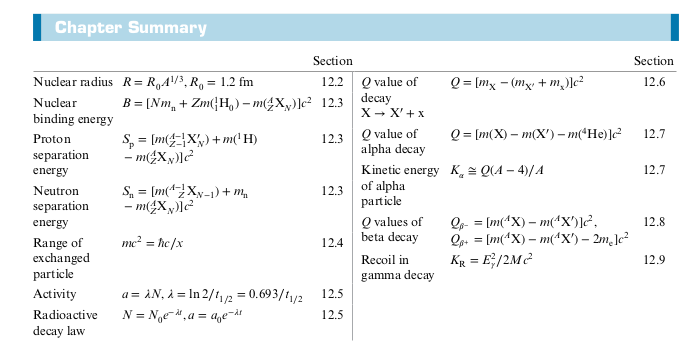

Chapter 12 Summary

13: Nuclear Reactions and Applications

Experimental Techniques in Nuclear Physics

- In nuclear physics, the energy range is in MeV or more

- Simple method

- Hold two plates with a potential difference

- Cons: Huge potential between the two plates

- Hold two plates with a potential difference

- Linear Accelerator (LINAC)

- Oscillating polarities for tubes

- Longer and longer tubes as you go down

- Largest: Stanford Linear Accelerator (SLAC)

- Cyclotron

- Two Half shells called Dees

- Magnetic Field used to make particles accelerate in a circular orbit

- As time passes, the particles reach larger and larger energies, so the orbits gets larger and larger

- Modern Particle Accelerator

- Two beams circling around in opposite directions

- Larger and larger energies mean uncertainty in energy get larger and larger

- Increases probability of more massive particles like the Higgs Boson

Types of Nuclear Reactions

Nuclear Reactions can be represented as follows

- If there is no external force, then energy, momentum, and angular momentum are all conserved

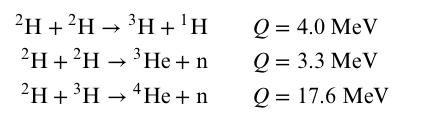

Nuclear Fusion

- Notice that the deuterium-tritium (DT) reaction releases the most energy

- Increasing

- Lawsons’ Criterion: Gives criterion for when fusion power exceeds input power

Magnetic Confinement

Inertial Confinement

- Focuses on increasing

- In the National Ignition Lab, 192 laser beams bring the DT to high densities in a 2mm diameter pellet in a pulse that is a few nanoseconds

- Compresses pellet to a density 100 times more than lead

Chapter 13 Summary